Servant Girl Annihilator

23 min read

Jack the Ripper was an infamous murderer whose story created a generational cult-like following amongst true crime lovers. As a result, there are numerous theories speculating on Jack's identity. One of the most fascinating, albeit far-fetched, is that Jack the Ripper stalked the streets of Victorian Austin three years before Whitechapel. In 1885, Austin, once a cow town with under 5,000 residents, abruptly tripled its size. In addition to population growth, the city had built opera houses, restaurants, hotels, a new state capital building, and three successful colleges. Underneath Austin's success, however, something sinister lay: an unknown killer brutally attacking, raping, and mutilating sleeping victims in their homes.

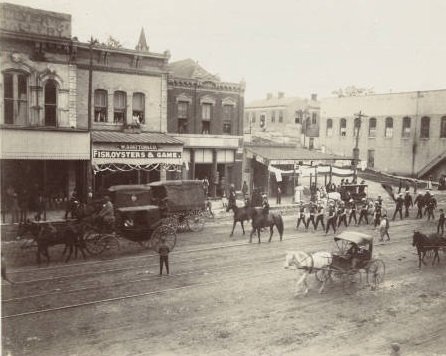

Congress Avenue 1888

Credit: DeGolyer Library, SMU

Introduction

The term "serial killer" was an unknown concept in the nineteenth century. It wasn't that the locals of Austin were unfamiliar with the idea of someone committing multiple murders: maniacs and outlaws would often make headlines after their psychotic rage sprees. But it was nearly impossible for them to believe a man could animalistically kill for pleasure, flip a personality switch and carry on without attracting attention. In the Fall of 1885, however, after a brutal attack on four people, police began to realize this killing was unlike anything they had encountered.

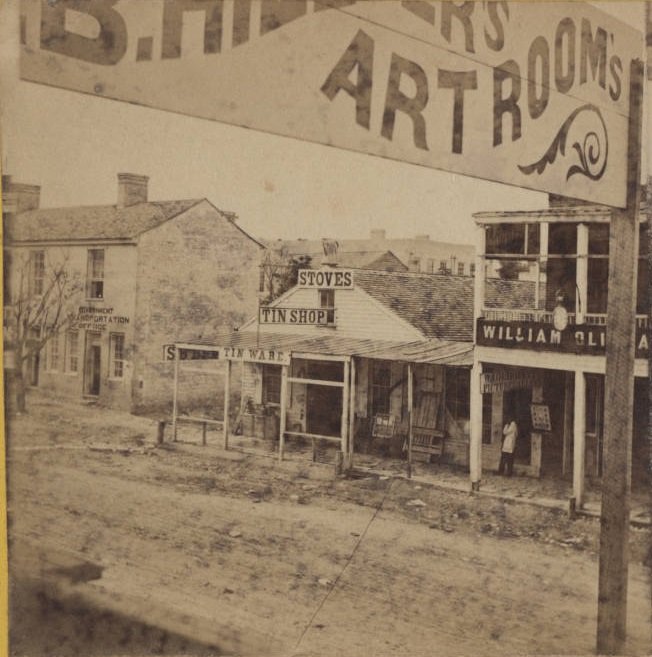

Pecan Street 1867-1886

Credit: DeGolyer Library, SMU

On September 28, W.B. Dunham, a journalist for the Texas Court Reporter, was woken up by a cry from the servants' quarters in the backyard. Dunham's cook, a young black woman, named Gracie Vance, lived in the quarters with her boyfriend, Orange Washington. In addition, they had two young servant women staying with them for the time being, Patsy Gibson and Lucinda Boddy. Figuring that Orange and Gracie were fighting, Dunham went to the back door and yelled at them to be quiet. Several minutes later, he heard a groan, so he grabbed his pistol and stepped outside. At the same time, Lucinda stumbled out of the shack, her head bloody, and screamed, "Mr. Dunham, we're all dead!"

Dunham's next-door neighbor ran into the backyard holding a lantern. He told Dunham that the noise had also awakened him and that he had already called the police. The two men stepped into the shack and held up the lantern. Patsy was lying on her side with blood flowing from her head, barely alive. Gracie was nowhere to be found, and Orange was dead. He was lying face down on the floor between the bed and the wall in a pool of blood. A bloody ax was on the bedspread next to him.

Two police officers responded to the distress call Dunham's neighbor placed and rode their horses to 2408 Guadalupe St, just past the University of Texas. When they arrived, they used lanterns to follow a bloody trail leading from the servants' quarters into another yard bordering the Dunhams'. The land was being used as a small horse pasture. As the police approached the stable, one of them stumbled over something. Putting their lanterns closer, they recognized it was the body of Gracie. She was beaten so viciously that her face was an unrecognizable mass of jelly. Beside Gracie was a brick covered with blood and bits of skin from her face. The only thing that wasn't bloodied on her body was a silver, open-face watch wrapped around her wrist.

Dr. C.O. Weller, a physician who lived in the neighborhood, arrived at the Dunhams' residence and examined the scene. Weller determined that each woman had been hit in the head once and Orange twice with a blunt object. Likely the back of the ax found in the servants' quarters. Besides the same head wound as Lucinda and Patsy, Gracie had been hit at least twelve times with the brick. Each blow shattered the bones in her face.

Unfortunately, these were not the first butchered victims Austin had uncovered in 1885. Four other servant women had been drug from their beds and mutilated. What was more strange is a witness had been left alive at each crime scene. For the first time since the killing spree had begun, some of the police officers talked openly that this likely wasn't the work of an ordinary criminal. A reporter even suggested that one man was carrying out these murders alone and anointed him the "Midnight Assassin." A killer, he wrote, who is "one of the most remarkable ghouls known to the death history of any section of the country."

Victims

The first murder occurred on December 30, 1884, at 901 W. Pecan St (now 6th St). Mollie Smith and Walter Spencer were hit in the head and knocked unconscious while sleeping. The residence belonged to a wealthy insurance agent named William Hall, and it was one of the more grand homes in Austin. Mollie, a twenty-five-year-old servant woman, cooked and cleaned for the Hall family six days a week in exchange for $10 a month and a place to stay. She lived in a tiny one-room servants' quarter in the backyard with her boyfriend, Walter.

When police arrived at the Hall residence the following day to investigate the attack, they immediately noticed a struggle. On the bed, the sheets and pillows were soaked with blood, dripping off one side and forming a pool on the floor. In addition, an ax stained with blood was at the foot of the bed. Finally, bloody finger marks were on the wall by the door leading to the backyard. Officer William Howe opened the door and followed a trail of blood more than fifty feet behind the outhouse.

Mollie Smith was lying on her back, her head nearly split open, with multiple stab injuries in her chest and stomach. Some of the wounds were deep enough to expose organs. There was so much blood that Mollie appeared to be floating in it. Walter was alive but in severe pain. He had five deep gashes in his head, and his orbital bone was fractured.

The second murder happened on May 6, 1885, at 302 E Cypress St. The home belonged to Dr. Lucian Johnson, a medical doctor and former state legislator. Thirty-one-year-old Eliza Shelley was employed as a servant and lived in a tiny cabin in the backyard with her three young boys. After she had prepared dinner for the Johnson family that night, she fed her sons the scraps she had collected, and they climbed into the bed they shared. Eliza and the two youngest children were at the head of the bed; her oldest son, seven, was at the foot.

Around 6 am the following day, Dr. Johnson's wife heard Eliza's children screaming. She sent her young niece, barely a teenager, to check on them. Within minutes, Mrs. Johnson's niece ran back screaming, so petrified that she couldn't speak. When Dr. Johnson returned from the market, he walked outside to the cabin and opened the door. Huddled in the corner of the room were three boys. On the floor next to the bed, covered with a blanket, was Eliza.

Sergeant John Chenneville arrived at the scene and ordered officers to carry Eliza to the backyard, where there was more sunlight. They removed the bedspread from her body only to discover she was wrapped in a second quilt. Finally, officers were able to get a look at her injuries. Part of Eliza's brain was seeping out of an ax wound in her right temple. Between her eyes was a small hole that looked like it had been made by a screwdriver or a thin iron rod. Eliza had also been cut up and down her body with a knife; some of the wounds were four inches deep. The blade had been sunk into her body and pulled directly out, severing blood vessels, muscle tissue, and cartilage.

Sergeant Chenneville's bloodhounds sniffed out what was described as "large, broad, barefoot tracks" leading to and from Eliza's cabin. Unfortunately, the dogs could not pick up a scent. So, Chenneville began to ask Eiza's seven-year-old son some questions. The boy said that he had been shaken awake in the middle of the night by a man wearing a white rag over his face with two holes cut out for eyes. The man commanded the young boy to put his head under a pillow and not to look up, or else he would kill him. Then, the man told him that he was leaving for St. Louis on the first train in the morning. After that, Eliza's son said he fell asleep, and his two little brothers had never woken up.

Of course, the police did not believe the boy's story; how could all three of Eliza's sons sleep through her being murdered? But, each time the boy was asked what had happened, he repeated the same story. Dr. Johnson, extremely distraught, came out to the backyard and told reporters that Eliza was an excellent woman. He described her as a hard worker who was reliable and honest. Johnson said he, his wife, and his children tended to treat Eliza as part of their family rather than a servant.

On May 22, only two weeks later, Rober Weyermann heard a low moan from his backyard on 302 E Linden St. He ran outside to find his cook, thirty-three-year-old Irene Cross, lying on the lawn. Her right arm was nearly severed in half, and she had a long horizontal gash across her forehead. It looked as if Irene's attacker had tried to scalp her. She tried to speak, but blood poured from her forehead into her mouth. Irene held on for a few days, eventually dying on May 25, 1985.

As with the murder of Eliza Shelley, police had to rely on another child witness. Irene's twelve-year-old nephew lived with her and slept in one of the cabin's two rooms. The boy said he opened his eyes to see the shadowy figure of a man coming through his door. He was holding a knife and quietly told the boy he wasn't there to hurt him. Then, after threatening Irene's nephew not to scream, he ran into her bedroom and left a few minutes later. The boy told reporters he believed the attacker was an overweight black man.

On August 30, at 300 E Cedar St, only one block from where Eliza Shelley was murdered, another attack ensued. Rebecca Ramey, a large, bodacious woman in her forties, was working for Valentine Weed. Rebecca and her eleven-year-old daughter, Mary, slept on pallets in the Weed's kitchen that night. Like so many other women in Austin that summer, they were terrified to sleep in the servant quarters. Unfortunately, no area was safe from the assailant, and in the middle of the night, Rebecca woke to see a dark silhouette standing over her.

Early the next day, Valentine Weed and his wife heard groaning from the kitchen. He opened the door to see Rebecca on her hands and knees with her head lowered to her chest. Part of her forehead was caved in, and blood flowed from two cuts in her left temple. Rebecca's jaw was crooked, and she could barely speak when the Weed's asked where Mary was. On the floor was a club wrapped in buckskin containing several ounces of lead packed in sand.

Valentine Weed grabbed his gun and asked his neighbor to investigate the backyard shed with him. When they looked inside, Mary was lying on the floor with her eyes partly open, staring at the two men with no expression. Blood was trickling out of her ears and nose. Valentine told his neighbor to stay in the backyard while his wife ran to get help from Dr. Johnson, and he rode his horse to alert Sergeant Chenneville.

Dr. Johnson, Chenneville, and a second doctor, Richard Swearingen, arrived and realized there was nothing they could do for the young girl. Mary's attacker had inserted a long iron rod into one of her ears, piercing the brain, and then pulled out the rod and jammed it into the other side, essentially lobotomizing her. Dr. Johnson cradled Mary's head until she passed away just as dawn arrived.

On September 28, Gracie Vance and her boyfriend, Orange Washington, were murdered, and their friends Patsy Gibson and Lucinda Boddy were brutally attacked in their sleep. As the case was being investigated, John Robinson arrived at the police department with his Swedish teenage servant girl. Early that same morning, the girl entered her quarters to discover her clothes scattered across the room and furniture upended. It was apparent that someone had been there. The girl went through her belongings, and the only thing missing was a silver open-face watch she had received from her father in Sweden.

One of the officers retrieved the silver watch found on Gracie Vance's wrist and showed it to the girl. She flipped the watch over, and engraved on the back was her name. When asked if she knew how it had ended up on the body of a murdered woman, she shook her head and said she didn't know who Gracie was. There was a long silence as the men at the police department stared at one another, trying to piece everything together.

On December 24, Moses and Susan Hancock sat by their fireplace, reading and sharing a piece of cake while their two daughters were at a Christmas party. Moses was a wealthy carpenter, and his wife, Susan, was often described as "one of the most refined ladies in Austin." They were in their early forties, and their daughters were ages fifteen and eleven. Moses and Susan went to bed around ten, sleeping in adjoining rooms, typical for the era. A gas lamp was left burning by the front door for their daughters, who arrived home a little after 11 pm. Just around midnight, Moses woke to a loud noise.

He entered Susan's room and saw that her bedding was on the floor, her clothes were scattered, and her window was open. Moses walked to the backyard and found Susan lying in a pool of blood. She had two deep wounds on her head; one had cut into her cheekbone, and the second had perforated her skull and sunk into her brain. Susan's right ear had also been punctured by a thin rod, but she was still breathing.

The Hancock's next-door neighbor, Harvey Persinger, helped Moses carry Susan into the parlor, and then he ran for help. Marshal James Lucy and a newspaper reporter arrived at the crime scene along with the Mayor and District Attorney. Within minutes, the Hancock's lawn was filled with men. Blood poured from Susan's mouth as physicians worked frantically to save her life, pressing bandages to her head wounds and giving her morphine to ease the pain. Then, as officers were still searching the backyard for evidence, Henry Brown, the night clerk at the police department, approached the residence on horseback at full speed. "It's Eula Phillips!" He shouted. "Her head has been chopped in two!"

Eula was seventeen and married to Jimmy Phillips, the twenty-four-year-old son of a successful Austin architect. Eula was frequently considered one of Austin's most beautiful young women, dressing in corset gowns and broad hats piled with feathers. The couple lived at 302 W Hickory St in one of the city's more lavish two-story homes, built and designed by Phillips' father.

Marshal Lucy and the other men arrived at the residence and were led to the backyard. Next to the outhouse was Eula's body, lying on her back with her nightgown pulled up and twisted around her neck. Because of this, police speculated the attacker must have used the nightgown to drag her across the yard. Eula had been struck directly above the nose by the blade of an ax, splitting her forehead open. Across the side of her head was another horizontal wound, and blood pooled around her. Immediately, officers noticed something about this crime scene that was unlike the rest. Across Eula's body were three pieces of firewood, two across her breast and one across her stomach. In addition, her arms were outstretched, almost as if she had been posed ceremoniously.

Lucy went back into the house and was led to a room where Jimmy, Eula's husband, was lying in bed with a large gash above his ear. He was in a daze and completely unable to communicate. A bloody ax was at the foot of the bed. Jimmy's mother, Sophie Phillips, told Lucy that she had heard her grandson, Tommy, crying around midnight. Tommy was ten-months-old and slept in the same bed as Jimmy and Eula. When Sophie opened the door to their bedroom, Jimmy was curled under a mess of bloody sheets, and the baby was sitting up and holding an apple, unharmed though his clothes were covered with blood.

After Lucy finished speaking with Sophie, he was shown a bloody bare footprint on the wood floor in the hallway outside Jimmy and Eula's room, right next to the door leading to the backyard. He ordered the wood planks containing the footprint to be removed and taken to the police station along with the ax. News of a double murder spread within minutes; Susan Hancock and Eula Phillips had been hacked to death, and white women were now being targeted. It wasn't long before the streets of Austin were filled with people in a panic.

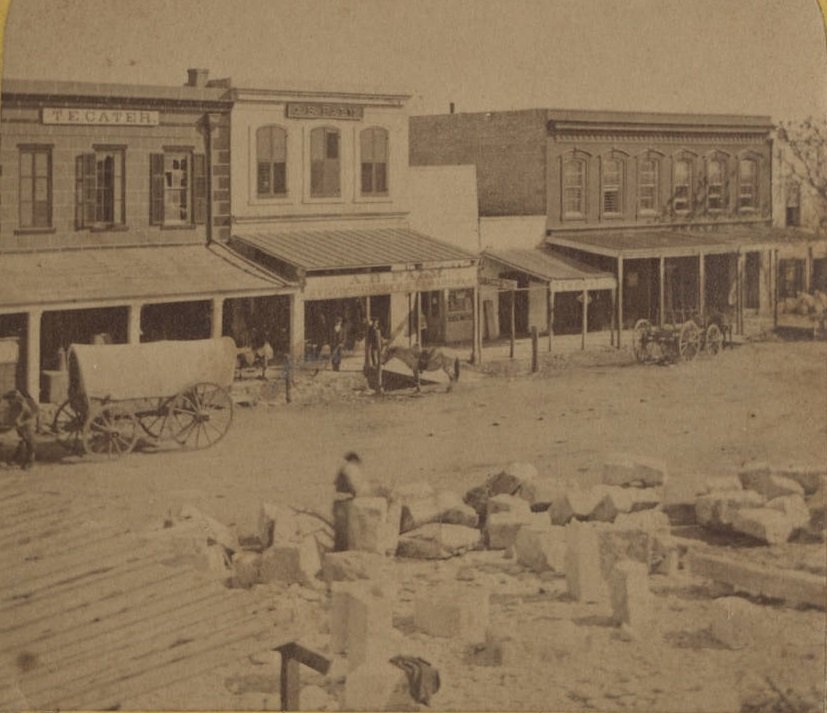

Congress Avenue 1867-1886

Credit: DeGolyer Library, SMU

Suspects

Marshal Lucy ordered Sergeant Chenneville and his officers to round up the usual group of black men who always seemed to be in trouble with the law. When they arrived at the police department, the men were asked to remove their shoes, place their feet in a bowl of ink, and step down on a piece of paper to see if their footprint matched the one found outside Eula's room. But, unfortunately, there were no matches, and all the men had alibis for where they had spent Christmas Eve.

On December 26, the story of the attacks went national, and there was more talk of the possibility that one man had committed the killings. Other reporters were now referring to him as the "Midnight Assassin," a term first used by a writer for the San Antonio Daily Express. Some citizens speculated that a patient at the State Lunatic Asylum had snuck out in the middle of the night, killed at random, washed in a creek, and returned to his room undetected. Others took note that all of the murders took place right before, during, or immediately after a full moon. In the 1800s, there was still a general belief that too much exposure to moonlight could cause someone to go mad. But, the case abruptly took on a new direction when a man named Thomas Bailes revealed to officials some information he had about Eula Phillips.

Thomas Bailes was a former U.S. marshal and assistant chief for a private detective agency in Austin, attesting to his character. Still, when officials heard his story about Eula, they couldn't believe it. Weeks before her murder, Thomas spotted Eula stepping out of a carriage and quickly entering a boarding house owned by Mae Tobin. Mae was an older woman who ran a brothel where men could rent a room by the hour. Police brought Mae in for questioning, and she arrived with her attorney, agreeing to reveal what she knew as long as she wouldn't be prosecuted for running her brothel. Mae acknowledged that Eula had come to her house weeks before her death and met with three lovers at different times, though Mae didn't know the names of the men. When asked about Christmas Eve, Mae said that Eula did come by but had quickly left when she told her the rooms were all booked for the night.

The Empire Livery and Sale Stable 1885

Credit: DeGolyer Library, SMU

Police knew that Jimmy had been an angry drunk, and with the knowledge of Eula's infidelities, they quickly formed a new theory. Jimmy must have gone out to one of the saloons, gotten drunk, and passed out when he returned home. Then, Eula took her opportunity to sneak out and meet one of her lovers at Mae Tobins. When she returned and went to bed that evening, Jimmy grabbed the ax from the woodpile, slammed it into her skull, then dragged her body outside and placed pieces of wood across her body to make it seem like Eula had been killed by the same crazed man who murdered the servant women. Jimmy then returned to their bedroom and hit himself in the head with the ax so the police would also believe he had been attacked. An arrest warrant was quickly issued, but Jimmy's doctor said he was still unable to speak or walk due to his head injuries. Officers ordered guards to wait outside his door to prevent him from escaping.

A couple of weeks later, Thomas Bailes, the same man who had information on Eula, went to officials regarding the Hancock case. According to him, Susan Hancock's killer was none other than her husband, Moses. When word spread, the citizens of Austin shook their heads in disbelief. The Hancocks were a quiet couple who never showed outward signs of marital struggles. Moreover, the odds of Moses committing an almost identical murder as Jimmy Phillips on the same night didn't line up. However, when Bailes explained what he heard, some thought Moses Hancock's arrest made sense.

Susan's sister, Mary Farwell, lived in Waco when she heard the news of what happened. Shortly after reading about Jimmy Phillips' arrest, she visited Waco's marshal and told him that her sister's life had not been peaceful for the last few years. Then she presented a letter she had found while cleaning up the Hancock's home after Susan's death. The month before her murder, she wrote to Moses that she was leaving him because of his alcoholism. Bailes speculated that Moses must have found the letter, became enraged, and decided to kill her before she left with their daughters.

On May 24, 1886, Jimmy Phillips' trial began. He was still pale from his slow, painful recovery and sat slumped over next to his defense team. Over the next three days, friends and family of the couple were brought in to testify about the abuse Jimmy inflicted on Eula when he drank. But, ultimately, the trial's only evidence was the bloody footprint cut from the floor. In closing arguments, Jimmy's attorneys said that if his prints did not match the one found at the scene, the court had no choice but to acquit their client. Jimmy removed his shoes, placed his foot in a bucket of ink, and stepped onto a pine board. When they compared it to the footprint found outside the couple's room that night, it was clear that Jimmy's foot was smaller.

After deliberating for a day and a half, the jury found Jimmy Phillips guilty of murder and sentenced him to seven years in prison. The courtroom gasped, and his attorneys said they would be filing for an appeal immediately. On November 10, the Court of Appeals announced they had reviewed the case. They agreed that the prosecutors had not presented proof that Jimmy had been aware of Eula's affairs, thus giving no motive for him to kill his wife. His case was returned to Austin's district court for a new trial. Jimmy was released on bail and moved back home with his father. Nearly four months after his release, a motion was filed by the district attorney to have the case against him dismissed. No further evidence had emerged to support a conviction.

In June 1887, Moses Hancock went on trial for the murder of his wife, Susan. His defense attorney was John Hancock, the same man who had defended Jimmy Phillips. He was so furious that Moses had been prosecuted that he took on the case for free. The council asked Moses's oldest daughter, Lena, to take the witness stand. She told the court that her family lived happily; although Susan was angry with Moses's drinking, he never laid a hand on her or their daughters. Lena then said that her mother had never found the courage to show her father the letter she had written telling him she was moving to Waco with the children. Instead, she had hidden the letter in the bottom of a box of fake flowers, where her sister, Mary, had found it. The authorities were wrong, Lena said; her father had no motive to murder their mother and destroy their family.

At the end of the trial, the defense attorneys brought in a surprise witness, Travis County sheriff Malcolm Hornsby. On February 9, 1886, a little over a month after the Christmas Eve murders, officers responded to a scene at a saloon in Masontown. Masontown was a small, black community just east of the Austin city limits. Nathan Elgin, a black man in his early twenties, had gotten into an argument with a woman, pushed her down, and dragged her to a nearby house, where he began to beat her. When an officer arrived, they tried to place handcuffs on Elgin's wrists, but he quickly turned around and struck the deputy in the head. Then, the officer pulled out his pistol and shot Elgin in the chest, killing him.

Hornsby said that when he arrived, he noticed Elgin was missing the pinky toe on his right foot; he remembered that the bloody print outside of Jimmy and Eula's room looked like it was missing a toe. Suspicious, Hornsby ordered a plaster mold of Elgin's foot be made so they could compare the prints side by side. Hornsby then said he believed the prints discovered in the alley behind the residence where Mary Ramey was killed also indicated the suspect was missing his right pinky toe. Therefore, in his opinion, Elgin's footprint was consistent with those found, and he believed they had identified their Midnight Assassin.

Nathan Elgin grew up in Austin and was known during his teenage years as troublesome. In 1882, he was arrested for writing a letter threatening to kill the deputy sheriff. However, no reports of Elgin being detained have been reported since then. At the time of his murder, he was married with two children and worked as a cook for the finest restaurant in Austin, Simon and Bellenson's. During Jimmy Phillips' trial, defense attorneys didn't mention Elgin's name, so why did they decide to do it now? Regardless, the lawyers closed their arguments, and after two days of deliberation, the jury was hung six to six. A day later, the vote changed to eight for acquittal and three for conviction, with one "doubtful." When no one would budge, the judge called for a mistrial

Credit: Austin Daily Statesman 3 June 1887

Walter Spencer, the boyfriend of the first victim, Mollie Smith, was also arrested and charged with her murder. Even though the perpetrator critically injured Walter when Mollie was axed to death. There was no evidence to sustain the case, and he was acquitted after a two-day trial. The police interviewed around 400 suspects but couldn't confidently charge them with any involvement in the killings, and the case grew cold.

Citizens in Austin spoke nervously about the possibility that the Midnight Assassin was still walking amongst them in disguise, but he never emerged. Since the Christmas Eve murders, there had been no more ax attacks. It seemed as if the killer had disappeared, but where had he gone? Then, on September 5, 1888, a story came over the news wires. A woman had been found severely mutilated in the lower-class district of Whitechapel in East London, 4,295 miles away from Austin.

New Era of Killers

The woman was Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols, a twenty-six-year-old sex worker in London. Two deep knife cuts had severed her throat down to the vertebrae. In addition, the killer stabbed Polly's vagina twice, and the lower part of her abdomen was ripped open by a deep, jagged wound, causing her organs to protrude. The suspect was a man who wandered through the Whitechapel district at night wearing a leather apron, stepping from the shadows to extort money from the sex workers and beating those who refused. A reporter for the Daily Statesman immediately noticed a connection between the murders in London and the servant girl murders in Austin. He commented that the murders had been "perpetrated in the same mysterious and impenetrable silence." The sex workers in Whitechapel had also described the man who attacked them as short and heavyset, which was the exact description given by Irene Cross's nephew after her murder in 1885.

Credit: CHRONICLE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

On September 8, a mutilated woman was found in an alley less than a mile from where Polly's body was discovered. Her name was Annie Chapman, and she was another sex worker with her throat severed by two deep cuts. In addition, the killer had cut her stomach open and ripped her small intestines out. During Annie's autopsy, examiners discovered that her uterus and sections of her bladder and vagina had been removed. After her murder, the Central News Agency in London received a letter written in red ink signed by "Jack the Ripper." The writer was antagonizing the police department and alluding to the murder of more "whores".

On September 30, a third sex worker, Elizabeth Stride, was found. A single incision measuring six inches across her neck had severed her left carotid artery, tissue, and trachea. The absence of mutilation to her body suggested her killer was interrupted during the attack. Forty-five minutes later, another mutilated and disemboweled body was discovered; Whitechapel sex worker Catherine Eddowes. Her throat was severed from ear to ear, and her abdomen was ripped open by a deep, jagged wound before her intestines were placed over her right shoulder. Catherine's face was also extremely disfigured; the killer had severed her nose, carved her cheeks, and removed parts of her right ear. In addition, her left kidney and uterus had been removed. The medical examiner who performed the autopsy on Catherine said the mutilation would have taken around five minutes to complete.

Police drawing of the body of Catherine Eddowes

Back in Austin, the Daily Stateman was still printing stories suggesting that Jack the Ripper was none other than the Midnight Assassin, who had also committed two murders within an hour of each other. Other American newspapers picked up on the story and started to push the London-Austin connection. Soon, newspapers in England ran headlines like "A Texas Parallel!" and detectives working the case were intrigued. One afternoon, a detective talked to an English sailor who had recently visited a local pub and encountered a peculiar Malaysian man. He was about 5 foot 7 inches, 130 pounds, and thirty-five years old. The man told him he had been working as a cook on the steamers at the English ports, and a woman in Whitechapel had recently robbed him. The man said, "unless he found the woman and recovered his money, he would murder and mutilate every Whitechapel woman he met."

Upon further investigation, it was discovered there was a Malaysian cook named Maurice who had worked at the Pearl House hotel in Austin. An employee at the hotel told a reporter that Maurice had worked there in 1885 and left sometime in January 1886, telling people he was headed to Galveston in hopes of finding a job on a steamer to take him to England. Although Maurice was rarely seen around Austin while he lived there, it is reported that several of the crime scenes happened just three or four blocks from the boardinghouse where he slept. The news was quickly cabled across the ocean, and London newspapers began publishing several articles concluding that a Malaysian cook was behind the Texas and Whitechapel killings. The police chief ordered his officers to find the man, but he was never located, and eventually, the department hit a dead end with the lead.

The original Malay newspaper clipping

Credit: JTR Forums

Moonlight Towers

At this point, several years had passed since the servant girl murders, but the city of Austin was still living in fear. Residents purchased electric burglar alarms, door locks, sleeping potions, and tonics. Then, in 1894, the newly elected mayor of Austin cut a deal with Detroit officials to purchase thirty-one artificial moonlight towers. Each tower was 165 feet tall and weighed approximately 5,000 pounds, with a ring of six high-powered carbon arc lamps on top. Unlike other cities that had put their arc lamps above railroad depots and shopping districts, Austin placed their lamps across the city to cover as much ground as possible. Residents feared that the artificial light would cause their crops to grow, their hens would start laying 24 hours a day, and many people began to carry umbrellas to protect their skin.

While the Midnight Assassin was never identified, the towers remain a permanent reminder of that terrible year. Today, the moonlight towers in Austin are the only surviving towers in the world. In 1970 the towers were recognized as Texas State Landmarks, followed by the remaining towers being inducted into the National Register of Historic Places. In 1993, the Zilker Park tower was featured in the film Dazed and Confused as the site of a high-school party, in which character David Wooderson played by Texas native Matthew McConaughey exclaims, “Party at the moon tower!” Locations of the remaining towers:

West 9th and Guadalupe St (SE corner)

W. 12th St. and Blanco St (SE corner)

W. 12th St. and Rio Grande St (NW corner)

W. 15th St. and San Antonio St (SW corner)

W. 41st St. and Speedway St (SW corner)

Zilker Park (used for Zilker Park Christmas Tree) (moved from Emma Long Metropolitan Park)

Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd. and Chicon St (SE corner)

E. 13th St. and Coleto St (NE corner)

Pennsylvania Ave. and Leona St (NE corner)

E. 11th St. and Trinity St (SE corner)

E. 11th St. and Lydia St (SE corner)

Canterbury St. and Lynn St. (NE corner)

Leland St. and Eastside Dr (SE corner)

Moonlight tower at 22nd and Nueces

Credit: Austin Explorer

Sources

Hollandsworth, Skip. The Midnight Assassin. Thorndike Press, 2016.

https://texashillcountry.com/west-texas-owlman-giant/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Servant_Girl_Annihilator

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_the_Ripper

https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/capital-murder/

http://www.servantgirlmurders.com/the-servant-girl-annihilator/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moonlight_towers_(Austin,_Texas)

https://austinot.com/austin-moon-towers

https://www.austinpostcard.com/moontower.php

https://www.historicmysteries.com/servant-girl-annihilator/