Ice Box Murders

40 min read

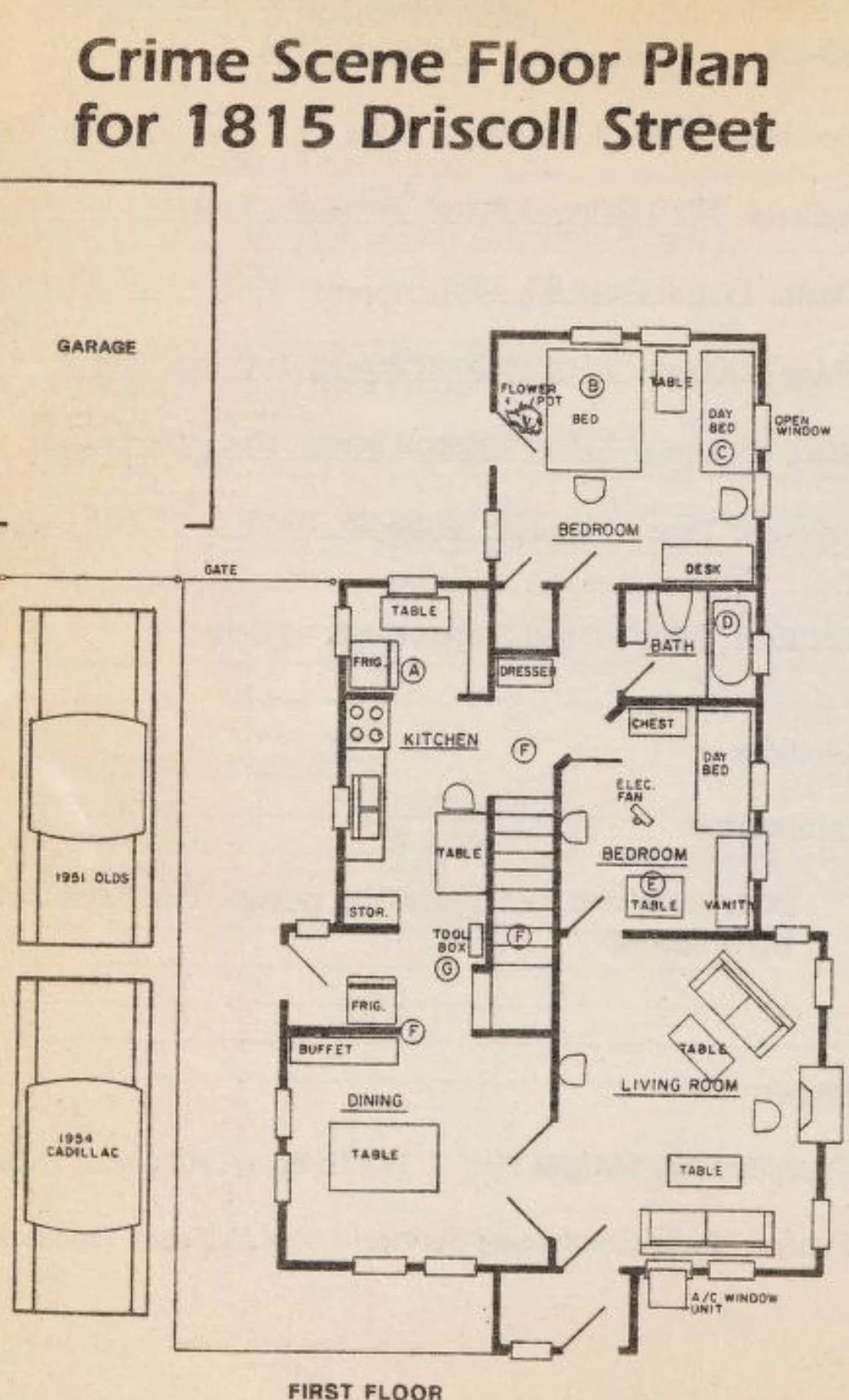

Inside a modest brick home at 1815 Driscoll Street, the dismembered bodies of Fred and Edwina Rogers were discovered neatly stored in their refrigerator. The couple's son, Charles Frederick Rogers, quickly became the prime suspect. However, before investigators could question him, he vanished without a trace. The case, later dubbed "The Ice Box Murders," remains open. In the decades that followed, new research suggested that Charles Rogers story extended far beyond Houston. Journalists, private investigators, and independent researchers uncovered connections linking him to the Civil Air Patrol, CIA-affiliated operations, and even the assassination of John F. Kennedy. My research into this case combines insights from Hugh and Martha Gardenier’s "The Ice Box Murders" and John R. Craig and Philip A. Rogers "The Man on the Grassy Knoll," along with FBI documents, CIA files, and the Warren Commission Report. Together, these sources create a complex portrait of a man who may have been more than just a reclusive son turned murderer; he could potentially have been involved in one of America’s greatest unsolved conspiracies.

1815 Driscoll Street

Source: Gardenier, Hugh; Gardenier, Martha (2003). The Ice Box Murders.

Ice Box Murders

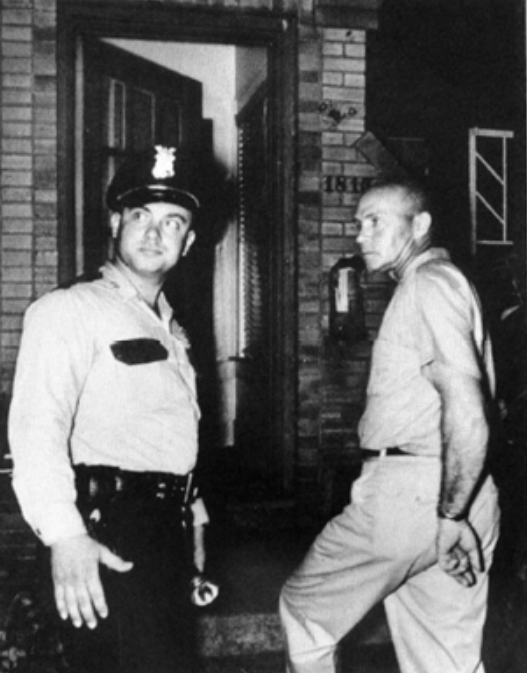

On June 23, 1965, officers C.A. Bullock and L.M. Barta responded to a welfare check at 1815 Driscoll Street in the Montrose neighborhood of Houston, Texas. Marvin Martin had not heard from his aunt, Edwina Rogers, for several days and was growing concerned. When the officers arrived, they noticed the blinds were drawn, and there was no response to their knocks. They went to the back of the house and discovered that the door was wedged shut from the inside with flowerpots.

Patrolman L.M. Barta and Marvin Martin, nephew of Edwina Rogers

Source: Gardenier, Hugh; Gardenier, Martha (2003). The Ice Box Murders.

The officers forced their way inside to find the house messy, but Marvin explained that this was normal for his 72-year-old aunt, Edwina, and her 81-year-old husband, Fred, who lived there with their 43-year-old son, Charles. However, when the officers entered the kitchen, they immediately sensed something was wrong. There was uneaten food on the table, a crowbar, and drops of blood on the floor. Officer Bullock, unable to explain his actions later, opened the fridge, which was packed tightly with unwrapped, washed meat. His initial thought was that the couple had butchered a hog. As he was about to close the door, he caught sight of something in the glass tray above the vegetable bin: the head of Edwina Rogers.

Detective James P. Paulk

Source: The Houston Chronicle

After recovering from the initial shock, Officer C.A. Bullock rushed outside to his patrol car and called for reinforcements. At 9:10 p.m., Detectives James P. Paulk and C.E. Smith arrived at 1815 Driscoll and took over the investigation. Within an hour, the house was filled with police officers, forensic teams, and members of the press. The body was removed from the fridge at 11:30 p.m. by Assistant Medical Examiner J.L. Turner. Shortly after the examination began, a second shocking discovery was made: in a brown paper sack was Fred's head. The fridge was so packed that it was initially difficult to identify the male torso among what was assumed to be Edwina's remains. As the medical examiners continued to remove body parts and arrange them on a plastic sheet, the extent of the crime became increasingly apparent.

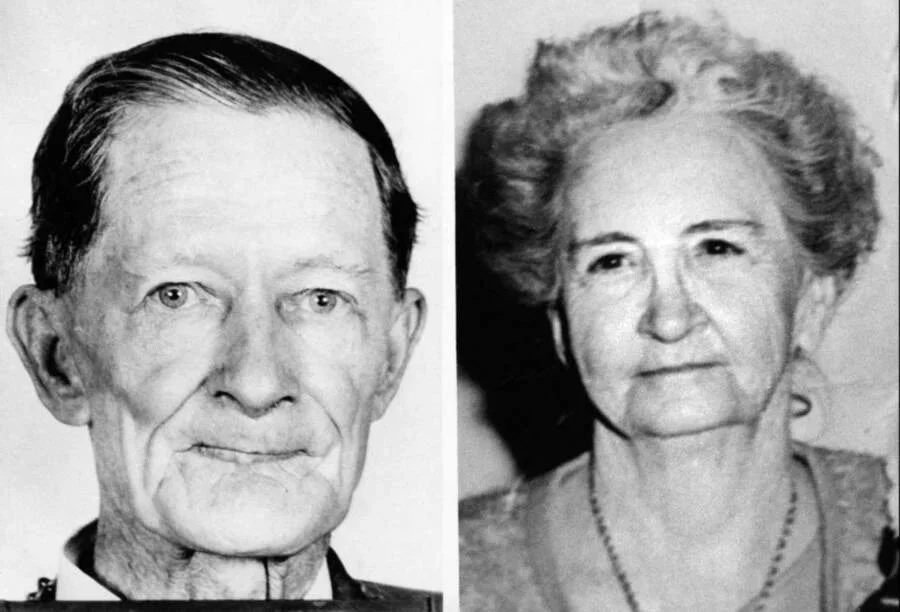

Fred and Edwina Rogers

Source: The Houston Post

Dr. Robert Bucklin conducted the autopsy in the basement of Ben Taub Hospital, located in the Texas Medical Center. Fred Rogers cause of death was bludgeoning. He had received so many blunt force injuries to his skull and face that he was barely recognizable. His eyes had also been removed with jagged excisions. Edwina, though she had also been bludgeoned and had a skull fracture, died from a gunshot wound to the head. Investigator Henry Ismonde determined Edwina had been alive for about twenty minutes between the incidents and had been attacked first upstairs. After Fred was killed, she was shot and dragged down the stairs to the bathroom to be dissected. It appeared Fred had been attacked downstairs in the bedroom while he was asleep, as there were no signs of a struggle.

Fred and Edwina's bodies had been meticulously dismembered and washed as if someone were preserving an animal. Each joint had been severed with a sharp instrument, their chests cut open, and their spines sawed in half. Edwina's breasts had been cut off and her sexual organs mutilated, while Fred's had been removed entirely. A fragment of Edwina's glasses was found deeply lodged in her brain from the shooting. The bullet had entered her skull above the left temple, just above her ear, and exited below her right eye.

The couple's missing organs were recovered in a nearby sewer two days later, after several residents complained to the city about a foul sewer odor. A public works crew discovered tissues clogging the sewer pipes, which appeared to be pieces of human skin, liver, fat, and lungs. They had been found in the direction of flow from the Rogers house, two blocks away at Woodhead and Vermont Streets. Suggesting the killer had disposed of the matter by flushing it down the toilet. Detective Thornton took the organs to the morgue for further analysis. Only the lung tissue could be positively identified as human, the rest had deteriorated too severely to be classified with certainty.

Chemical testing conducted by chemist Floyd MacDonald revealed that the downstairs bathtub was a focal point of the crime. The room had been scrubbed clean so that no blood was visible to the naked eye. Still, traces had been found in the sink, toilet, and walls leading across the hall into the kitchen. A path that would have been taken as their bodies were dragged piece by piece. Despite obvious efforts to clean up, it was apparent that the bodies had been dissected in the kitchen. The large dining table next to the refrigerator had saw marks and scratches on the surface; a luminol test confirmed this had been the operating label. The contents from the fridge have been removed and stacked around the kitchen to make room for Red and Edwina's bodies. No fingerprints were found anywhere in the house.

Investigators initially thought there had only been one victim.

Source: KHOU TV

Near the stairway, a clawhammer, a 20-inch keyhole saw, and a straight razor were found in a toolbox. Testing revealed that the saw had been used to cut through bone, and a small portion of flesh and hair was found on the hammer and handle of the hammer was cracke. Indicating this was the instrument used to bludgeon the couple. A bloody mop and clothes were found soaking in a pail of soapy water in the right basin of the kitchen sink. Another pail was found near an open window with several bloody rags, two cotton dresses, and a bloodstained clear plastic raincoat. The upstairs bathroom also revealed traces of blood, indicating the killer had cleaned up in the room, too. The only locked room in the house belonged Fred and Edwina’s son, Charles.

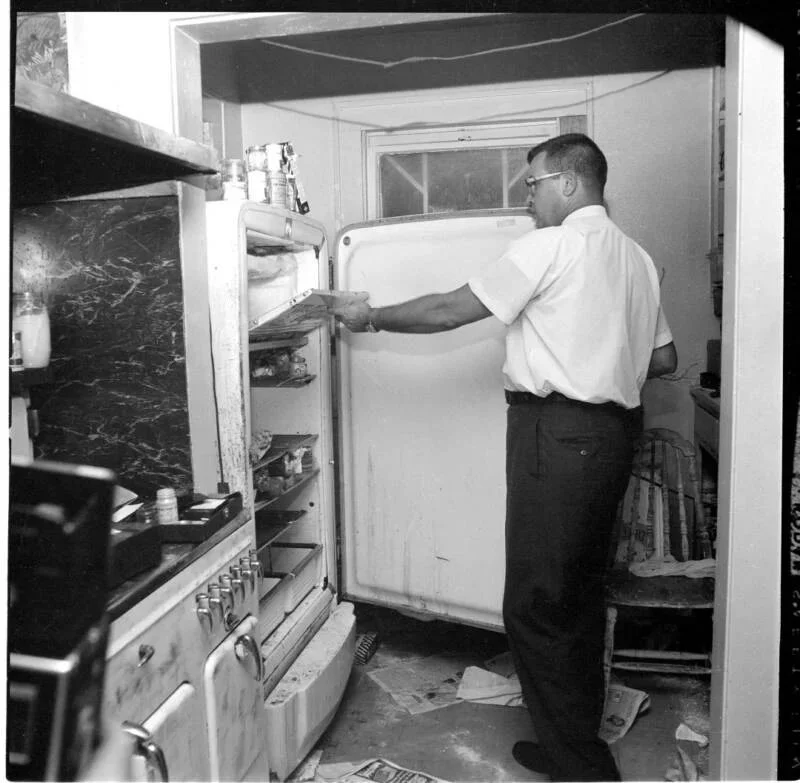

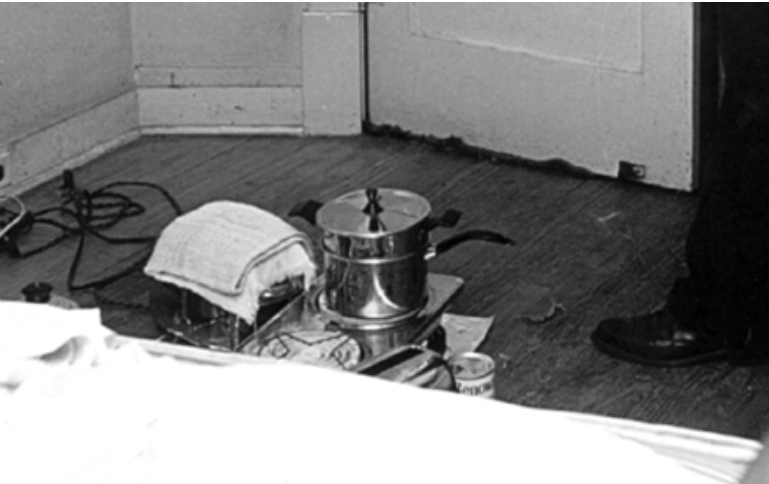

Investigation

In Charles Rogers’ room, a two-burner hot plate, a toaster oven, and a coffee pot were neatly arranged on a nightstand next to his bed, alongside remnants of a meal. He had a supply of coffee, four eggs, and some utensils stored on a piece of tinfoil, indicating that Charles preferred to eat his meals alone. A pack of cigarettes, clothing, and a fedora hat were scattered across his unmade bed. Charles owned an extensive collection of musical instruments, including a ukulele, a trombone, a saxophone, a violin, and a small electric organ. Other items found in his room included several electronic books, a Texas A&M Cadet Corps cap, an honorable discharge certificate from the U.S. Navy, an expired ham radio license, and a commercial pilot's license for a single-engine aircraft.

A hotplate and other small cooking appliances where found in Charles Rogers room.

Source: Gardenier, Hugh; Gardenier, Martha (2003). The Ice Box Murders.

On the bottom shelf of the nightstand, there were bullets and a Colt .22 Huntsman automatic pistol hidden under a handkerchief. The gun had recently been fired, with a shell lodged in the chamber, causing a jam. Ballistic tests confirmed that the Huntsman was the weapon used to kill Edwina. Unfortunately, this finding was of little value, as federal firearm records were not maintained in 1965, and the gun had been wiped clean of fingerprints.

Charles Rogers nightstand

Source: Gardenier, Hugh; Gardenier, Martha (2003). The Ice Box Murders.

Detectives Paulk and Smith conducted a further investigation of the home. In the front bedroom, they found a single bed, several old photographs, and women's cosmetics placed on top of the dresser. An old electric fan was positioned on the left side of the dresser, continuing to circulate air. Smith noted that the fan didn't seem to be hot, which raised questions about how long it had been running. On the chest of drawers across the room was a pair of aluminum-framed women's glasses. Both lenses had blood spots on them, and the left earpiece was torn off. However, there was no blood spatter on top of the chest, the floor, or the back wall. The condition and placement of the glasses suggested that the victim did not place them there herself.

The room appeared to have been searched; papers were scattered across the floor, and the drawers of the dresser were left open with their contents rummaged through, but it was unclear what had been taken. Was this a burglary gone wrong or a deliberate cover-up? As Paulk inventoried the primary bedroom, he began to share the same concerns. The room contained four windows, and the window on the east wall was open nine inches with the screen unfastened. On the bed, two packages of letters had bloodstains on them. Several boxes and a small desk also appeared to have been rifled through. Some of the scattered documents were business records, but once again, it remained unclear what had been taken.

Outside the house, there was a detached two-story garage stocked with Stanley Home cleaning products. Edwina, a saleswoman for the company, used the garage as her warehouse to fulfill orders. Several bottles of cleaning products were found inside the home and were used by the killer to clean up the crime scene. The second floor of the garage contained electronic equipment, ham radio parts, and a sophisticated ham radio station with an antenna running along the ceiling to maximize transmission power. In the driveway, there were two broken-down cars: a 1951 turquoise Oldsmobile and a 1954 green Cadillac.

The neighbors were of little help. Although the Rogers family had lived there since 1950, most residents were barely aware of them. One woman, who had lived on the street for seven years, didn’t even realize that the elderly couple had a son. While some neighbors acknowledged Charles Rogers, they commented that he was seldom seen. Another neighbor mentioned that the only thing she ever observed Fred Rogers doing was feeding the squirrels and birds every morning around 8 a.m. Edwina Rogers, however, was more active in the community. In addition to being a Stanley representative, she was a regular member of the Lord’s Church nearby on Indian Street. Other residents remarked that Fred and Edwina frequently had disagreements, which often escalated to their front yard, where Edwina would stand in the doorway shouting at Fred as he tried to leave. Several of their next-door neighbors moved away due to the intensity of the arguments. Eventually, a privacy fence was built between the properties to help block some of the noise. This seemed to be effective, as no one heard any sounds of distress coming from the house on the night of the murders, nor did they hear the sound of a gunshot.

An occasional maid and driver for the Rogers family reported to the police that she had known the family for several years and had never seen their son, Charles. She stated that his bedroom was off-limits and referred to an incident that occurred a year earlier, in which Edwina mentioned that she had not seen her son for five years. This was surprising, as Charles had been living in the house with them during that time. Six years prior, there had been a confrontation in which Fred had attacked Charles, and Edwina had intervened when Charles began choking Fred. The incident upset Charles so much that he ultimately refused to speak with his parents. He would leave the house early in the morning before they woke up and return late at night. The maid observed that Edwina would communicate with Charles by slipping notes under his bedroom door.

A few days later, a woman who was a Stanley dealer and had known Edwina for a few years, as well as having met Fred during business trips, called the Rogers house on Wednesday at about 9 a.m., twelve hours before the bodies were discovered. A man answered the phone and said Edwina was not home, then promptly disconnected the line without identifying himself. She recognized the voice as being familiar from previous calls when Edwina was out. She assumed the voice belonged to Charles, though she couldn't be certain since she had never met him. With this information, along with the trail of blood leading upstairs to his room, the remnants of a recently eaten meal, and the open window on the second floor, investigators began to narrow their focus in on Charles Rogers as being the suspect.

Charles Rogers

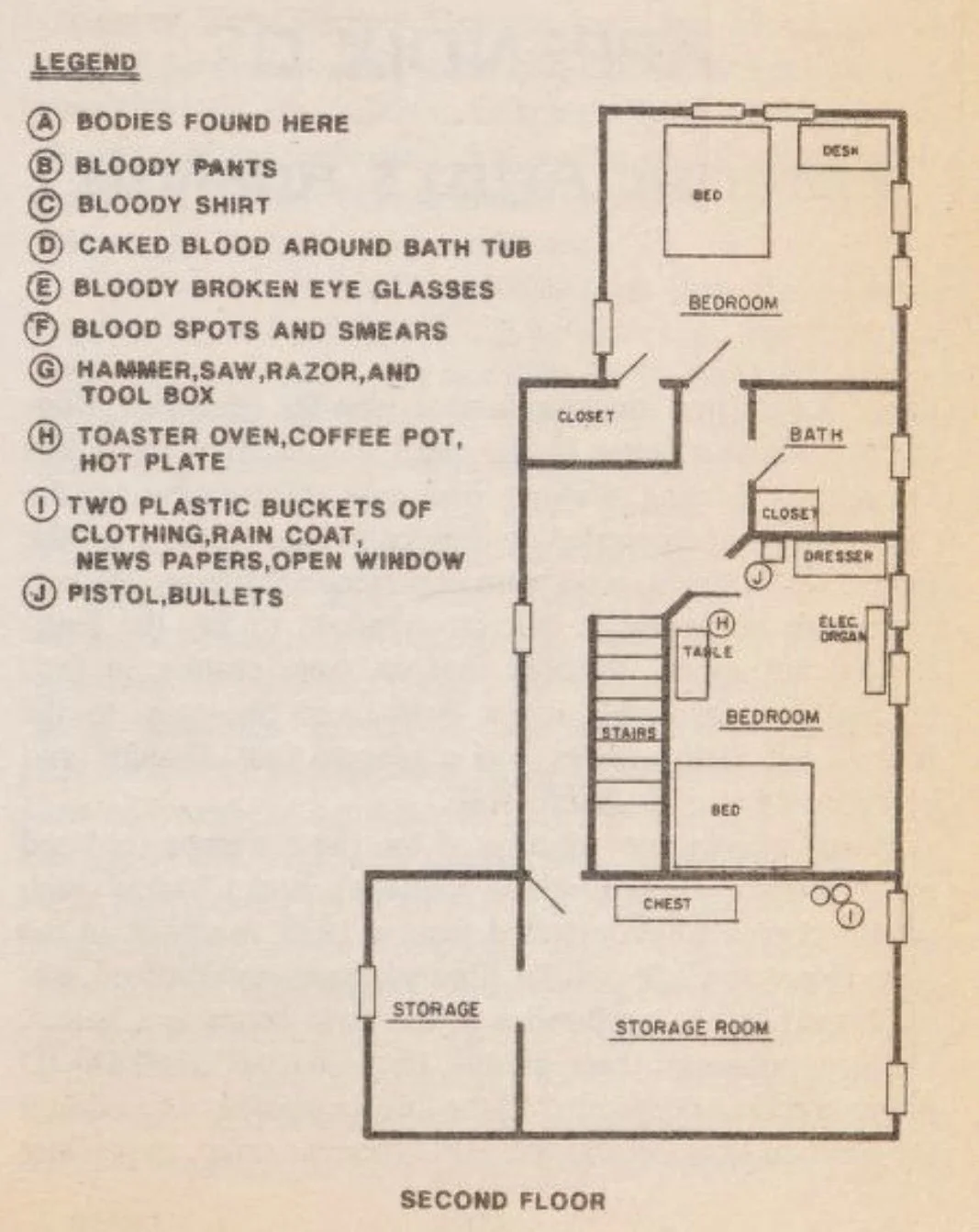

Charles Frederick Rogers was born to Fred and Edwina Rogers on December 30, 1921. On August 8, 1929, the family went on a trip to San Antonio to visit Fred's mother. One of their friends, Leonard Adams, was driving the car because Fred and Edwina had not yet learned to drive. Fred shouted when a deer jumped out from the side of the road, causing the driver to veer off and crash into a tree. Tragically, Charles's 10-year-old sister Bettie, who was also in the car, did not survive the accident. Charles held resentment towards his father for Bettie's death. During his elementary years, Charles attended Trinity Lutheran, a private church school. Small for his age, he was often bullied, which made him reserved; his voice would usually tremble when speaking to strangers. Throughout his childhood, his parents moved frequently—at least five times before he turned 13—and they constantly fought. Charles would sometimes stay with Edwina’s brother, Edwin Harmon, in Shiro periodically during the 1930s and 1940s.

Charles and Bettie Rogers in 1922

Source: Gardenier, Hugh; Gardenier, Martha (2003). The Ice Box Murders.

From an early age, Charles had excelled in mathematics and demonstrated exceptional technological aptitude. After graduating from high school in 1939, Charles attended Sam Houston State's Teacher College in Huntsville. In 1941, he began working as a seismographer for Shell Oil and subsequently withdrew from Sam Houston State University. In August 1942, he enrolled at Texas A&M to continue his education, but enlisted in the Navy on October 18, 1942. During World War II, Charles served as a pilot in the Office of Naval Intelligence. He was honorably discharged on December 20, 1945, with the rank of Radio and Electronics Technician First Class. In January 1946, he enrolled at the University of Houston, where he earned his bachelor's degree in nuclear physics. After completing his degree, Charles worked for Shell for an additional nine years. However, on April 15, 1957, he abruptly quit without explanation, and from that point forward, his life became increasingly mysterious.

U.S. Navy 1943 - before assignment to the USS Barnes

Source: Gardenier, Hugh; Gardenier, Martha (2003). The Ice Box Murders.

Neighbors on Driscoll Street remarked that they were uncertain if Charles had a job. When they saw him, he was typically walking at a fast pace, well-dressed, and carrying a brown paper bag. His signature look included a high-crowned gray felt fedora, which was quite fashionable in the 1960s. He was five feet five inches, 145 pounds, with brown hair and blue eyes. Other relatives in the Houston area also had little information to share about Charles' habits and personality, describing him as a complete hermit. Strangely enough, Charles had a cousin in the Houston Police Department, Detective George Harmon of the forgery division. He was Edwina's nephew and had not seen Charles in ten years. He told reporters that Charles was “like a morning fog...he just faded in and faded out.” Associates said that Charles had a talent for finding gas, oil, and gold for the companies for which he worked and spoke seven different languages, but was not much of a socializer.

The pilot's license discovered at the house provided detectives with another potential lead regarding their suspect. They tracked the license number to Hull Airport, a small hangar located near Sugar Land on the southwest side of Houston. The owner, Don Hull, stated that Charles had stored a Cessna 140, a two-seat single-engine aircraft, at the airport during 1958 and 1959. Hull mentioned that he had flown with Charles once and described him as an excellent pilot, though not particularly talkative. According to Hull, Charles claimed to be a salesman for a water purification equipment company and frequently made flights to Austin for work. The last time Hull saw Charles was about two years prior, in 1963, at which point he noted that Charles had sold his plane. Hull indicated that Charles typically flew his own aircraft and never rented one.

Detectives contacted all the airports, aircraft dealers, and rental agencies in the Houston area. Still, none had any information about Charles Rogers. They also searched all airports within a two-hundred-mile radius of Houston, operating under the assumption that if he had landed anywhere, a document would exist, but nothing was found. Police also called every water purification company in Houston. Yet, none of the companies had a record of him in their files.

On July 4, George Wagner, an employee of the Fluor Corporation located at 3137 Old Spanish Trail, reported a significant lead to the homicide unit. Wagner, along with two other employees, had been looking at a picture of Charles Rogers published on the front page of the Houston Chronicle. They believed that Charles was the same man who had requested a job application at Fluor on the afternoon of Thursday, June 24. They described him as having a receding hairline, mascara-darkened eyebrows, and a thin mustache. He identified himself as Anthony Pitts and expressed his interest in working as a welder either in Japan or Australia. The company informed him that the only available job options were in Canada, Iran, or Iraq. Pitts mentioned that he had previously worked for Shell in Canada and was not interested in returning there; instead, he preferred a job overseas. Throughout the interview, he appeared nervous and asked if he could complete the application at home and return it by mail. However, an application from Anthony Pitts was never received.

For the press, the story died hard. There had been no worthy leads or developments in the Rogers case since 1965. Their files were buried under the bottomless pit of unsolved cases stacking up on the desk of the chief of homicide, Captain L.D. Morrison, Jr. Eventually, he pulled the plug on the investigation. Detective Paulk made a plea for an arrest warrant for Charles Rogers, arguing that the physical evidence, the murderer's familiarity with the crime scene, and experience told them that the Rogers were likely murdered by their son. Morrison countered that there was no incriminating evidence and that they didn't want to arrest the wrong man. Charles had no prior arrest records or convictions, and he had never been committed to any mental institution.

The summer of 1965 was one of the worst on record for the reputation of the Houston Police Department. They were being scrutinized for their professionalism and administrative effectiveness with issues such as corruption and political interference. Morrison was in a challenging position because the more his department investigated the background of the Rogers, the more likely his men were to uncover something he didn't want to explore.

The house at 1815 Driscoll Street remained unoccupied for many years. There were occasional reports of break-ins and disturbances at the property. On August 27, 1970, two patrol officers responded to a call regarding the house. They found both side doors unlocked, and on the dining room wall, someone had scrawled in large letters, "I killed my mother and father. I am the killer." The vandal had rummaged through furniture drawers, scattered papers throughout the house, and pried open the garage door. In July 1975, Texas State District Judge Arthur C. Lesher declared Charles legally dead to resolve a civil probate case involving forty-seven heirs to the Rogers estate. This decision facilitated the sale of the property, allowing the city of Houston to condemn and demolish the house. The lot remained empty until February 1994, when an investor purchased it and built condominiums on the site.

Detective Paulk was subpoenaed to testify at a hearing, stating that no leads had developed since the murders. Charles Rogers had not attempted to work using his social security number, nor had he renewed his pilot’s license with the Federal Aviation Administration. The FBI also reported that they were unable to find any information about Charles. They indicated that if he were to be located, he could still be arrested as a material witness, as there is no statute of limitations on murder. Among the detectives, there was speculation that Charles had escaped to Mexico or Canada, or that he might have been a victim himself and disposed of in a different location than his parents.

All of the original detectives who conducted the investigation have since passed away. Over the years, psychologists at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston attempted to analyze the case on four separate occasions, but they were unable to draw any new conclusions from it. Approximately 40% of homicides remain unsolved nationwide. The case remains open, with Charles as the sole suspect. However, this is where our story takes a dramatic turn.

One of the resources I consulted for this case is the novel "The Man on the Grassy Knoll", written by private investigators John R. Craig and Philip A. Rogers and published in 1992. In their book, they claim that Charles Rogers, Charles Harrelson, and Chauncey Holt were the infamous “three tramps” photographed and arrested in Dealey Plaza following the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22, 1964. The authors further assert that Charles Rogers murdered his parents because his mother was tracking his telephone calls and had beenmore suspicious of him.

While I must admit this is likely one of hundreds of conspiracy theories surrounding JFK, there’s something uniquely compelling about the connections Craig and Rogers describe. In an effort to validate their claims, I went down a long rabbit hole, combing through FBI and CIA files from the National Archives and pages of the Warren Commission Report. Ultimately, I found myself questioning the official narrative. I’ve come to believe that Lee Harvey Oswald was set up—a scapegoat in a much larger operation—and that there were, in fact, multiple shooters in Dallas that day.

CIA

Throughout the Deep South, particularly in Texas, the hysteria of the Red Scare persisted well into the 1960s. As late as 1966, anyone employed by the state or attending a state-sponsored event was required to sign a loyalty oath, affirming that they were not communists and did not belong to any other groups advocating violence to overthrow the U.S. government. Charles Rogers was significantly influenced by the anti-communist movement that swept across the nation. Charles joined the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) in the mid-1950s, a volunteer civilian auxiliary of the U.S. Air Force open to all interested civilians. According to Craig and Rogers, it was through the CAP that Charles crossed paths with David Ferrie, the eccentric commander of the Moisant Squadron in New Orleans. They met several times during regional missions and training sessions. Ferrie was only a few years older, but the two connected immediately, united by their intense hatred of communism.

In 1957, Charles sought a new career path and viewed government work as a promising opportunity. He had previously been approached by the CIA and contacted their headquarters in Washington to request an application—an initiative Ferrie believed would be well received. Ferrie’s name appears repeatedly in documents housed within the National Archives relating to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Though the government denies it, he has long been suspected by New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison of having ties to the CIA and potential involvement in covert operations. On July 27, 1955, 15-year-old Lee Harvey Oswald joined the Moisant Squadron in New Orleans.

David Ferrie

Source: The TImes-Picayuna archive

In their book, Craig and Rogers recount that Charles was interviewed for a potential contract position with the CIA by a man named Leopard. During that era, most covert agents began their careers this way, working on a per-assignment basis rather than receiving a full-time salary. This arrangement also provided a better cover for their activities. Leopard took note of Charles's naval background, as well as his experience in cryptography and radio operations, his patriotic feelings, and his strong opposition to communism. Discerning Charles would make a great addition to their agency.

The CIA contacted Charles's personal references. However, since Charles was not very social and struggled to come up with names, he mentioned to his mother that he was applying for a government job. He asked if Edwina's ministers, Reverend Elmer and Marietta Gerhart, would be willing to serve as references. Although the Gerharts didn't know Charles very well, they assured Edwina that they would be happy to help. Soon after, two men arrived at their doorstep. Elmer wasn't entirely sure which agency they represented. Still, he had a strong suspicion they were from the CIA, as he had a longtime friend who was a retired agent.

Charles's application was approved, and he began training as an undercover agent assigned to Latin American operations. His ability to speak multiple languages served him well. The men he worked with knew him by various aliases, including "Carlos Rojas," "Carlos Rigel," and "Ricardo Montoya." They commented that he could be frighteningly aloof; he would sit in the cockpit and not utter a single word to his copilot. Many believed he was either a Cuban exile or a professional hitman.

In 1963, Charles was briefed on an operation being carried out in Mexico by Guy Bannister, a private investigator and former FBI agent who was a friend of David Ferrie. Bannister was interested in infiltrating the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, which was providing support for the Cuban Revolution's attacks against the United States. On the evening of September 25, Charles Rogers introduced himself as "Carlos Rojas" to two men approaching him. He recognized one of them as Charles Voyde Harrelson, while the second man was a young CAP cadet named Lee Harvey Oswald, whom he had seen before at Moisant Airport. The plan involved setting Lee up through a complicated process known as "sheep dipping," a military intelligence term referring to the creation of a false identity for an agent, with or without their knowledge. Charles was deemed ideal for the assignment because he bore a slight resemblance to Oswald.

Guy Bannister

Source: Find a Grave

Charles explained to Oswald that he needed his personal identification and the fifteen-day Mexican tourist visa that he had recently obtained for a covert mission in Mexico City. Oswald handed them over without further questions, as Bannister had informed him that such documents might be required; using false identities and aliases helps to obscure the activities of their organization. Charles called a cab and took Oswald and Harrelson to Alamotel Courts, dropping them off before directing the cab to the Continental Trailways Station. On September 26, using Oswald’s name, Charles boarded bus #5133 in Houston, which departed at 2:35 a.m. for the Mexican border. He made sure to mingle with the other passengers as they woke up to solidify their recollection of meeting "Lee Oswald."

Lee Harvey Oswald

Source: NARA / President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection

Charles arrived in Mexico City on September 27, where he applied for a transit visa at the Cuban consulate, claiming he wanted to visit Cuba on his way to the Soviet Union. The Cuban consular officials insisted that "Lee" would need approval from the Soviet authorities. However, he was unable to obtain prompt cooperation from the Soviet consulate. After five days of moving between consulates—which included a heated argument with a Cuban consular official, impassioned pleas to KGB agents, and some scrutiny from the CIA—he was eventually informed by a Cuban consular officer that his visa application was unlikely to be approved. The official remarked that a person like Oswald was "doing harm" rather than aiding the Cuban Revolution. Charles left Mexico City on Transportes del Norte bus #332 at 8:30 a.m. and arrived in Laredo at 1:30 a.m. on October 3. He then boarded Greyhound bus #1265 at 3:00 a.m., which was bound for Dallas.

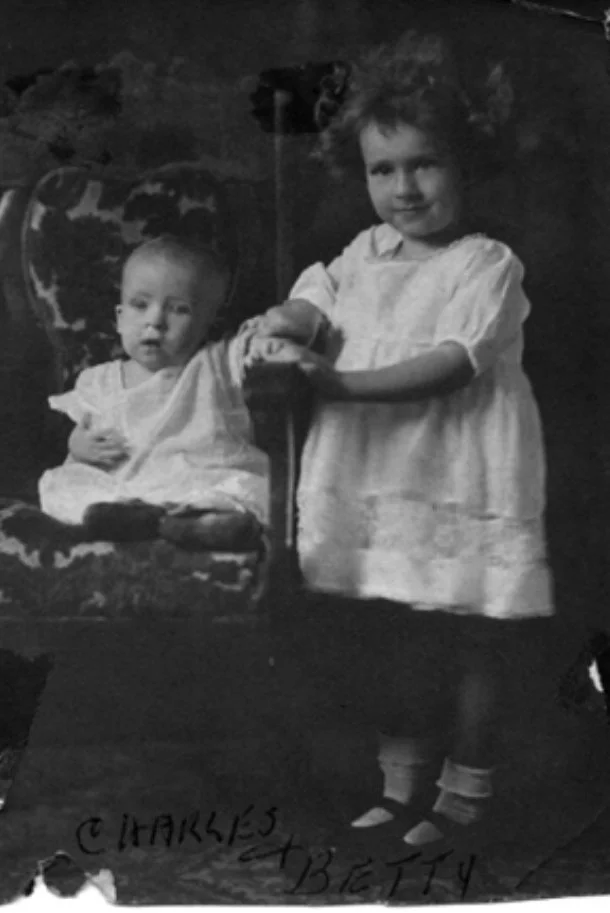

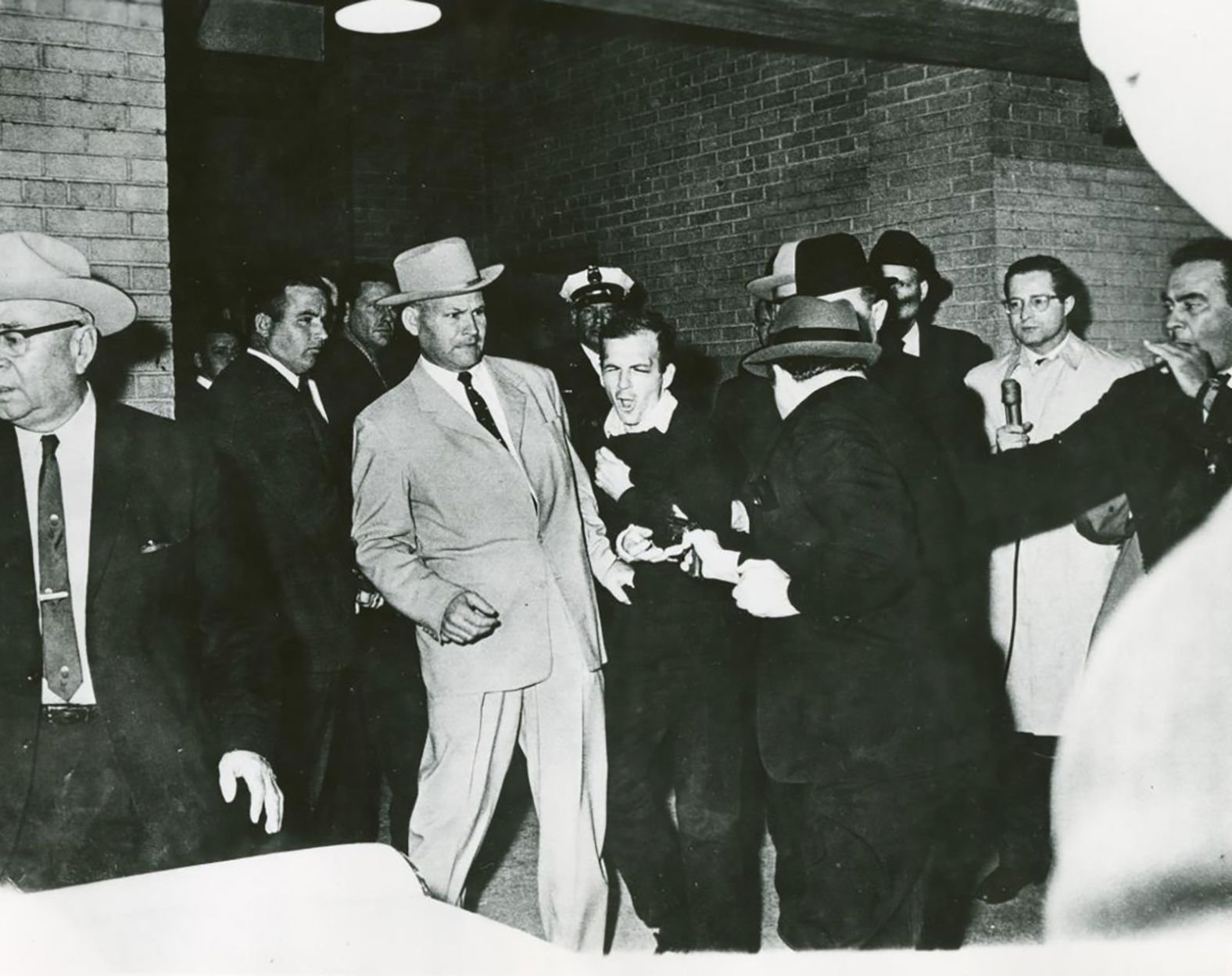

On November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas at Dealey Plaza. The fatal shot struck him from behind, devastating the back of his head in an instant. The now-infamous 8mm footage captured by Abraham Zapruder documents the horrifying moment in stark, unflinching detail. In it, a stunned Jackie Kennedy can be seen climbing onto the rear of the limousine—instinctively reaching for a fragment of her husband’s brain amidst the chaos and disbelief. Shortly after President Kennedy was shot, three men were photographed by several newspapers in the Dallas area while being escorted by police near the Texas School Book Depository. Since then, various allegations have arisen regarding the identities of these men and their involvement in a conspiracy to assassinate Kennedy. In their book, Craig and Rogers suggest that the men were actually Charles Rogers, Charles Harrelson, and Chancy Holt, a CIA operative who was in Dallas to deliver counterfeit Secret Service credentials.

The "three tramps" being escorted to the Sheriff's office

Source: University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History

According to their theory, Charles Rogers and Charles Harrelson fired their rifles almost simultaneously from behind the picket fence on the grassy knoll. They struck President Kennedy, hitting him once in the throat and once in the head. After firing, they ran towards the railroad switching yard, discarding their guns to an accomplice whose job was to drive away and dispose of them. Lee Bowers, the yard supervisor, saw the two men jump onto a boxcar just as the train was departing. He ordered the train to be stopped via radio, and the police quickly arrived to search the boxcars. Although the men were arrested, they were soon released by the police, who stated that they were merely hobos in the wrong place at the wrong time. The next day, Charles Rogers called from Dallas to Houston to inform David Ferrie that their plans had changed. Ferrie had been waiting near a pay phone at the Winter Wonderland skating rink, expecting to rendezvous with Charles and another shooter to flee to Central America.

While President John F, Kennedy was riding in an open limousine in downtown Dallas on his way to give a speech for his upcoming reelection, he was shot and killed.

Source: The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

In the frantic hours following President Kennedy's assassination, Lee Harvey Oswald slipped out of the Texas School Book Depository, where he worked, and vanished into the streets of Dallas. About forty-five minutes later, Officer J.D. Tippit spotted a man matching who matched the description of the shooter responsible for killing Kennedy walking through the Oak Cliff neighborhood. When Tippit pulled over to question him, Oswald drew a revolver. He fired four shots, killing the officer instantly before fleeing on foot. The city was now in chaos—its president dead, a police officer murdered, and the suspect on the run. Oswald ducked into the nearby Texas Theatre, where he did not buy a ticket, drawing the attention of the staff due to his agitated behavior. Moments later, police flooded the dimly lit theater with their guns drawn. After a brief struggle—during which Oswald shouted, "This is it!"—he was subdued and dragged from the building. Within hours, he was formally charged with the murders of both President John F. Kennedy and Officer J.D. Tippit.

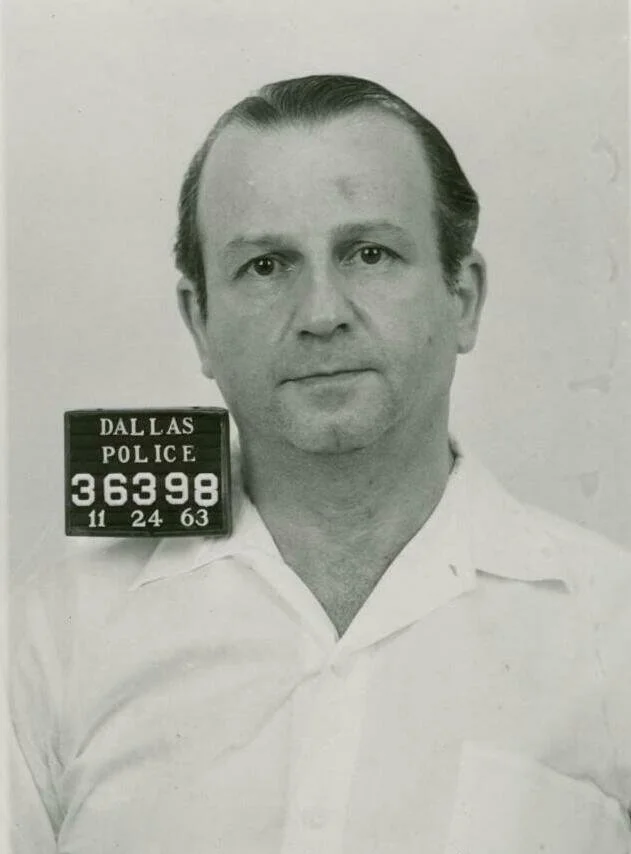

On the morning of November 24, 1963, detectives escorted Lee Harvey Oswald through the basement of the Dallas Police Headquarters. He was being transferred to the county jail under tight security. At 11:21 a.m., as cameras rolled live across the nation, a man suddenly stepped out from the crowd. Jack Ruby, a Dallas nightclub owner, raised a .38 revolver and fired a single shot into Oswald's abdomen at point-blank range. The basement erupted in chaos. "Jack, you son of a bitch!" one detective shouted as officers wrestled Ruby to the ground. Oswald, drifting in and out of consciousness, was rushed by ambulance to Parkland Memorial Hospital — the same hospital where President Kennedy had been pronounced dead just two days earlier.

At 1:07 p.m., Oswald was declared dead. Dallas Police Chief Jesse Curry announced the news in a televised broadcast, marking yet another shocking twist in an already bewildering week for the nation. Ruby later claimed that he acted out of grief, insisting he shot Oswald to spare Jacqueline Kennedy the pain of returning to Dallas for a trial. However, this explanation has long been questioned. Rumors circulated that Ruby had ties to the CIA and the Mafia, and that he was friendly with David Ferrie. According to some accounts, Ruby and Ferrie were even supposed to meet after the assassination.

Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald, who is being escorted by Dallas police. Detective Jim Leavelle is wearing the tan suit. This photograph won the 1964 Pulitzer Prize for Photography.

Source: Dallas Times Herald

Investigation of the JFK Assassination

According to an extensive report by the U.S. House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA), Jack S. Martin, a private investigator and friend of David Ferrie, informed several investigators on November 24, 1963, that Ferrie had known Lee Harvey Oswald for years and may have been his instructor in the Civil Air Patrol (CAP). The report came after an incident in which Martin was out drinking with Guy Bannister the night before. The two men got into a heated argument over stolen files, and Bannister pistol-whipped Martin. He was injured quite badly and checked into Charity Hospital to treat his wounds. Martin suggested that Ferrie had given Oswald instructions on how to use a rifle and had possibly hypnotized him into shooting the President. He also claimed that Ferrie was in Dallas on the day of the assassination.

During an interview with FBI agents in New Orleans on November 25, 1963, David Ferrie denied having any contact with Lee Harvey Oswald while he was associated with the CAP. Ferrie claimed that he served as commandant from 1953 to 1955 and believed that Oswald was not a member of his squadron during that time. When shown a photograph of Oswald, Ferrie said the profile view appeared vaguely familiar. Still, he did not recognize the full-face images. Ferrie gave various accounts of his trip to Texas on the night of the assassination.

Oswald in his Civil Air Patrol uniform, annotated on the reverse in blue ballpoint by his mother, “Lee, age 15 1/2 Civil Air Patrol picture taken in N. O. La. [New Orleans, Louisiana]

Source: Marguerite initially sold the photo to Dr. John Lattimer, a notable researcher of the Kennedy assassination. Picture sold at RR Auction in 2017.

When questioned by the FBI, Ferrie explained that he and two friends drove 350 miles to the Winterland Skating Rink in Houston, which is approximately 240 miles from Dallas, that evening. Ferrie mentioned that he had been considering the feasibility of opening an ice skating rink in New Orleans for some time and wanted to gather information about the ice rink business. He stated that he introduced himself to the rink manager, Chuck Rolland, and spoke with him at length about the costs associated with the installation and operation of the rink.

Ferrie confirmed that he had known Jack Martin for the past two years, describing Martin as a paranoid alcoholic who frequently interfered in his affairs. On November 26, Martin informed the FBI that the information he had previously provided about Oswald and Ferrie was fabricated. He admitted to concocting the story after reading newspapers and watching television, acknowledging that he had no specific details to support his suspicions. On November 28, 1963, Chuck Rolland was interviewed by the FBI. He reported that a man named Mr. Ferrie had contacted him by phone on November 22, 1963, inquiring about the skating schedule. Ferrie mentioned that he was coming from out of town and wanted to skate in Houston. On November 23, between 3:30 and 5:30 p.m., Mr. Ferrie and two companions arrived at the Winterland Skating Rink. Rolland and Ferrie had a brief conversation, but they did not discuss the cost of owning a skating rink.

In a second interview on November 28, David Ferrie told the FBI that he felt embarrassed and concerned about the lack of air cover during the Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba. He expressed disappointment in President Kennedy. Ferrie stated that he was very outspoken and may have used a colloquial phrase, saying, "He ought to be shot." Still, he insisted that he never made any plans to kill the President. Ferrie also criticized any President who rides in an open car, noting that someone could easily hide in the bushes and shoot at the passengers. Two weeks later, Ferrie provided an additional statement. He claimed again that, to the best of his knowledge, he had not met Lee Harvey Oswald while he was a member of the Moisant Squadron of the CAP. If he had met Oswald, it would have been a very casual introduction. Ferrie added that he had not seen Oswald in recent years.

The FBI interviewed approximately twenty people to investigate whether Lee Harvey Oswald had any connections to David Ferrie. However, they did not reach a definitive conclusion. One of those interviewed was Edward Voebel, who was Oswald's closest friend during his teenage years. Voebel confirmed that he and Oswald attended CAP meetings together in 1955. However, his statements to the FBI about whether Ferrie was their instructor were inconsistent. After learning about these allegations, Ferrie contacted several of his former CAP associates to gather information about Oswald. Former cadet Roy McCoy informed the FBI that Ferrie had visited him to inquire about photographs of the cadets, as he wanted to see if Oswald appeared in any pictures of Ferrie's squadron.

Some of this information eventually reached Jim Garrison, the District Attorney of New Orleans, who had grown increasingly skeptical of the official account of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination. In September 1964, the Warren Commission released its 888-page report concluding that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone and that there was no evidence of a broader conspiracy. Garrison, however, openly challenged those findings. He argued that it was impossible for a single gunman to have fired all the shots that struck the President. Beyond the now-infamous “magic bullet theory” put forth by the Commission, 51 witnesses present in Dealey Plaza reported hearing gunfire from the direction of the grassy knoll—casting serious doubt on the lone-shooter narrative.

View from the picket fence on the grassy knoll of Dealey Plaza

Source: Maiya Beeson

In December 1966, Garrison interviewed Jack Martin, who claimed that during the summer of 1963, David Ferrie, Guy Banister, Lee Harvey Oswald, and a group of anti-Castro Cuban exiles were involved in operations against Castro's Cuba. These activities included gun-running and burglarizing armories. As Garrison continued his investigation, he became convinced that a group of right-wing extremists, including Ferrie, Banister, Jack Ruby, and Clay Shaw, was involved in a conspiracy with elements of the CIA to assassinate Kennedy. Garrison later asserted that the motive behind the assassination was anger over Kennedy's efforts to secure peace settlements in both Cuba and Vietnam. He also believed that Shaw, Banister, and Ferrie had conspired to set up Oswald as a patsy in the JFK assassination.

On February 22, 1967, just days after a newspaper published a story about Garrison's investigation, Ferrie was found dead in his apartment. In his apartment, authorities discovered two unsigned, undated typed letters. The first letter was a lengthy rant about the justice system, beginning with, "To leave this life is, for me, a sweet prospect. I find nothing in it that is desirable and, on the other hand, everything that is loathsome." The second note was addressed to Al Beauboeuf, a friend of Ferrie's, to whom he passed down all his possessions. New Orleans Parish Coroner Nicholas Chetta and pathologist Ronald A. Welsh conducted the autopsy. They concluded that there was no evidence of suicide or murder; instead, Ferrie died from a massive cerebral hemorrhage caused by a congenital intracranial aneurysm that had ruptured at the base of his brain. Upon learning of the coroner's findings, Garrison remarked, "I suppose it could just be a weird coincidence that the night Ferrie penned two suicide notes, he died of natural causes."

In 1978, HSCA began reviewing all interviews conducted by the FBI, concluding that their investigation had not been thorough and exposed massive inconsistencies made within the Warren Commission report. One individual interviewed by the committee was Jerry Paradis, the former recruiter for the New Orleans Lakefront CAP unit. Notably, during an FBI interview on November 25, 1963, David Ferrie recommended Paradis as a CAP member who could confirm whether Lee Harvey Oswald had been involved in the unit led by Ferrie. According to the report from his FBI interview, Ferrie stated that during the period he served as commander of the squadron, Jerry C. Paradis was the recruit instructor and trained all the squadron recruits. Ferrie provided the Bureau with both the home and business addresses of Paradis to assist agents in conducting the interview.

In his interview with the committee on December 15, 1978, Paradis stated that he had never been contacted or interviewed by the FBI about his past involvement with the CAP, including his associations with Lee Harvey Oswald and David Ferrie. He also mentioned that no other investigators had ever questioned him regarding this matter. Paradis indicated that Oswald attended numerous CAP meetings, where Ferrie served as the instructor. Ferrie was consistently present during the time Oswald was part of the squadron. Paradis asserted that there were "at least 10 or 15 meetings" where both Oswald and Ferrie were present. He told the committee, "Oswald and Ferrie were in the unit together. I know they were there because I was there." He further emphasized, "I specifically remember Oswald. I can remember him clearly, and Ferrie was heading the unit then. I'm not just suggesting they may have been there together; I am saying it is a certainty." In 1993, the PBS television program Frontline obtained a group photograph taken eight years before the assassination, which showed Oswald and Ferrie at a cookout with other CAP cadets. Committee investigators also found five additional witnesses who confirmed that Oswald had been present at CAP meetings led by Ferrie.

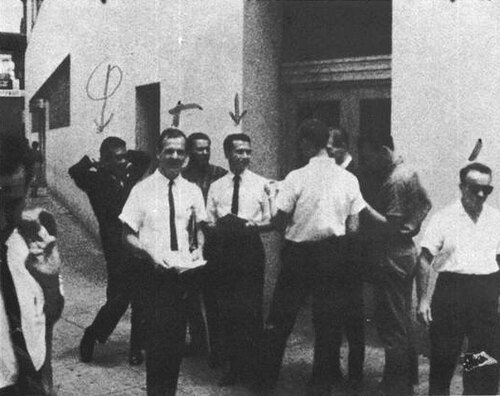

Lee Harvey Oswald (far left) and David Ferrie (bending over, wearing a helmet) at a cookout in New Orleans at the Civil Air Patrol in 1955

Source: The photograph was taken by Chuck Frances, a fellow CAP member. Frontline obtained this photograph from John B. Ciravolo, Jr., of New Orleans. Ciravolo was also a CAP member in 1955 and says he was in the same unit with Oswald and was standing right in front of him in the photo. Ciravolo also identified David Ferrie.

After leaving the New Orleans Police Department, Guy Banister established his own private detective agency, Guy Banister Associates, Inc. In June 1960, he relocated his office to 531 Lafayette Street, located on the ground floor of the Newman Building. Around the corner but located in the same building, with a different entrance, was the address 544 Camp Street, which would be found stamped on the pro-communist Fair Play for Cuba Committee leaflets that were found distributed on August 9, 1963, by Lee Oswald. In 1978 the HSCA also investigated the connection between Oswald and Banister at the Camp Street address. The committee wrote that it "could find no documentary proof that Banister had a file on Lee Harvey Oswald, nor could the committee find credible witnesses who saw Lee Harvey Oswald and Guy Banister together. There are, however, indications that Banister at least knew of Oswald's leafletting activities and probably maintained a file on him."

Lee Harvey Oswald Distributing Pro-Cuba Flyers in New Orleans on August 16, 1963

Source: The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

The CIA, along with the Mexican police, closely monitored Oswald's movements throughout his visit to Mexico City. Declassified documents reveal evidence that the CIA knew someone had been impersonating Oswald in calls to the Soviet embassy. Further records describe Oswald’s appearance upon arriving at the embassy as being around 35 years old, with an athletic build and receding hairline. However, Oswald was actually 23 years old and slender. When the CIA was asked to produce a picture of Oswald, they claimed thet were unable to locate him at any of their surveillance stations. Instead, they produced a photograph of a "mystery man” who was clearly not Oswald. CIA documents also reveal that Lee Harvey Oswald spoke "terrible, hardly recognizable Russian" during his meetings with Cuban and Soviet officials. Oswald lived in Russia from 1959 to 1962 and was known by his friends and family to speak fluent Russian. It’s also important to note that Oswald’s wife, Marina Nikolayevna Oswald Porter, was Soviet born and had immigrated to the U.S. after marrying Oswald.

While the Warren Commission concluded that Oswald had visited Mexico City and the Cuban and Soviet consulates, questions about whether someone was posing as Oswald were severe enough to be investigated by the HSCA. Later, the committee agreed with the Warren Commission that Oswald had visited Mexico City and concluded that "the majority of evidence tends to indicate" that Oswald had visited the consulates; however, the committee could not rule out the possibility that someone else had used his name to gain access to the consulates.

The Warren Commission found no evidence connecting Jack Ruby's killing of Lee Harvey Oswald to any larger conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy. The Commission also looked into rumors that Ruby and Oswald knew each other and that Oswald had been seen at Ruby's Carousel Club. Ultimately, the Commission concluded that the witnesses who claimed a connection between Ruby and Oswald were not credible, and there was no solid evidence linking the two men. Additionally, the Commission noted that Ruby did not have significant ties to organized crime and determined that he acted independently when he killed Oswald.

In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) re-examined the events surrounding Lee Harvey Oswald's assassination by Jack Ruby. The committee concluded that Ruby's act of shooting Oswald was not spontaneous, as it involved at least some degree of premeditation. They also believed it was unlikely that Ruby entered the police basement without assistance, even if those providing help did so without knowledge of his intentions. The committee expressed concern about the apparently unlocked doors along the stairway route and noted that security guards had been removed from the area nearest the garage shortly before the shooting occurred. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting that the Dallas Police Department withheld relevant information from the Warren Commission regarding Ruby's entry during Oswald’s transfer.

G. Robert Blakey, the chief counsel for the HSCA, stated, "The most plausible explanation for Jack Ruby's murder of Lee Harvey Oswald is that Ruby had stalked Oswald on behalf of organized crime, trying to reach him on at least three occasions within forty-eight hours before he finally silenced him." Given Ruby's network of contacts, his connections to anti-Castro figures, and his rumored interactions with individuals linked to the CIA, some investigators believe that Ruby was cleaning up loose ends — ensuring that Oswald, whether he was a participant or a scapegoat, would never have the chance to speak.

Jack Ruby

Source: Dallas Police Department photographic records

According to Craig and Rogers, the FBI overlooked another lead during their investigation. On September 25, 1963, two men arrived at the Lord's Church in Houston around 9:30 p.m. One man had dark hair, stood just under six feet tall, and was slender. The other was taller, had blond hair and was very handsome. They introduced themselves to Elmer and Marietta Gerhart as Lee and Charles. The men explained that they had been traveling from New Orleans on their way to Mexico and were supposed to meet their friend Carlos at the bus stop, but he hadn’t shown up. The Gerharts, moved by sympathy for the visibly exhausted young men, invited them inside the church for food and rest. After about forty-five minutes, Lee asked to use the telephone. He returned moments later, saying he had reached Carlos, who would meet them down the street in ten minutes. As the two men left, Elmer and Marietta watched from a window. They saw them approach a figure standing beneath a tree—a man in a suit and fedora, cigarette in hand. When he turned toward the light, the Gerharts recognized him as Charles Rogers. The three men then walked west towards Commonwealth Street.

Nearly two months later, on November 22, 1963, the Gerharts were at home when news broke that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in Dealey Plaza. The next morning, as Marietta unfolded the newspaper, she froze. On the front page was a photograph of the alleged assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald—the same man who had sat at their table in the church that night. Elmer immediately called the Houston FBI office to report what had happened. The agent who answered told him that they were overwhelmed with calls but would pass the information along. A week passed with no response. When Elmer called again, he was told that their report had been forwarded to the Dallas office and someone would be in touch. Frustrated and uneasy, Elmer turned to a trusted friend named Carl, a retired CIA operative. When Elmer explained what had happened, Carl spoke in a measured, almost guarded tone. “Elmer, you and Marietta have done your duty" he said. "I am asking you as a friend, to drop it, now. Let the government handle it. Leave it alone." He refused to elaborate, and the conversation ended there.

Lee Harvey Oswald after his arrest in Dallas, November 22, 1963.

Source: AFP/Getty Images

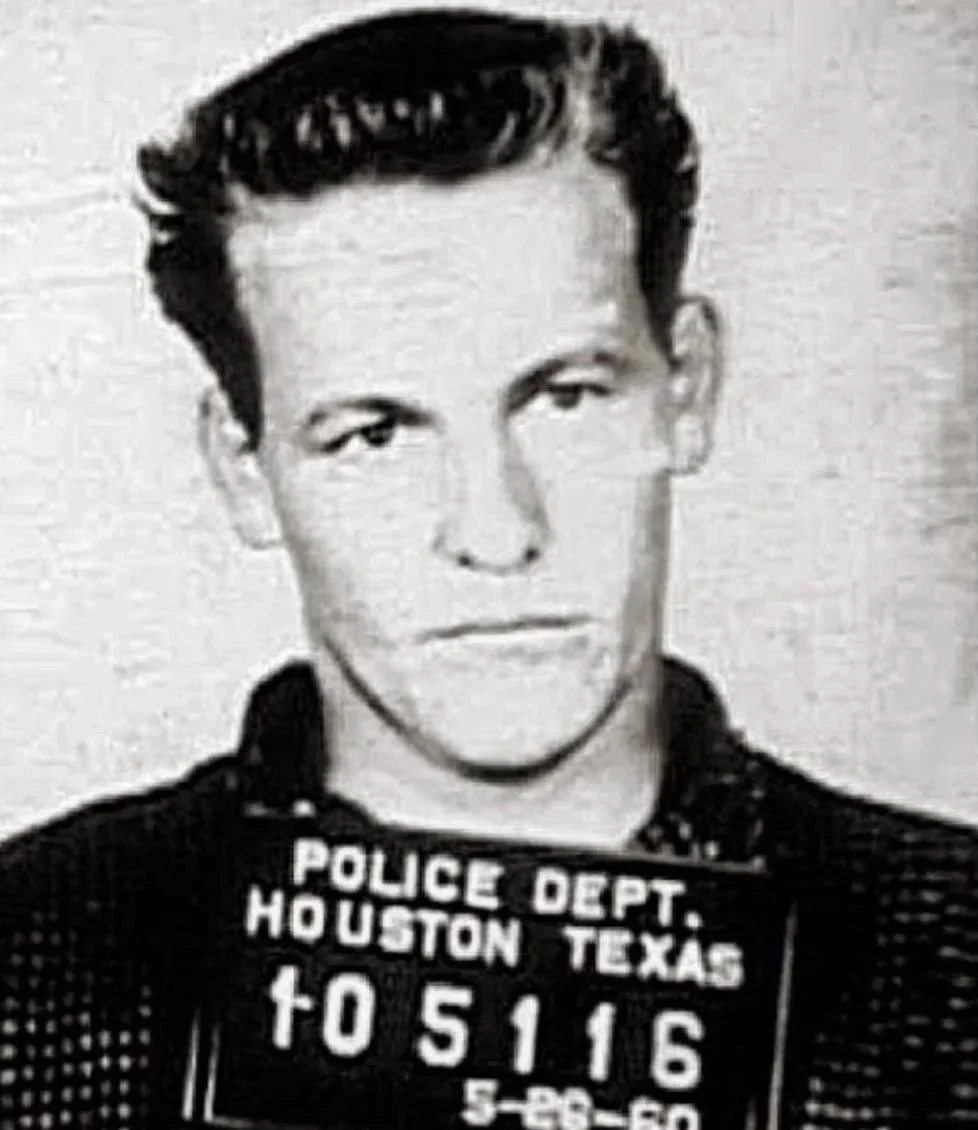

In September 1980, Charles Harrelson surrendered to police after a six-hour standoff in which he was reportedly high on cocaine. During the standoff, he threatened suicide and stated that he had killed both Judge Wood and President John F. Kennedy. A lawyer named Joseph Chagra later testified during Harrelson's trial that Harrelson claimed to have shot Kennedy and drew maps depicting his hiding spot during the assassination. Chagra said he did not believe Harrelson's claim, and the FBI discounted any involvement by Harrelson in the Kennedy assassination. In 1982, Harrelson told Dallas TV station KDFW-TV, "Do you believe that Lee Harvey Oswald killed President Kennedy, alone, without any aid from a rogue agency of the U.S. government or at least a portion of that agency? I believe you are very naive if you do."

Charles Harrelson mugshot 1960

Source: Texas State Historical Association

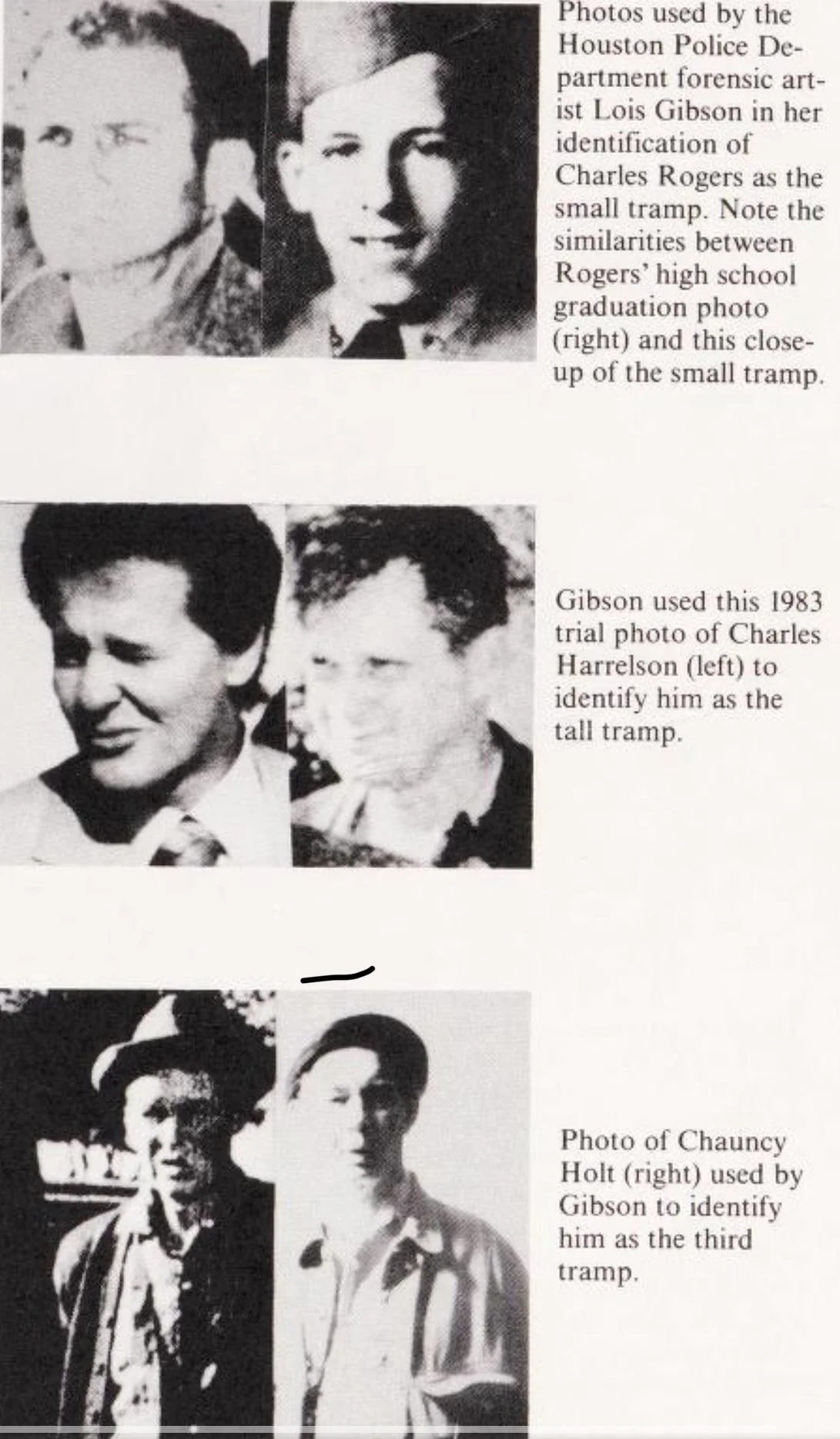

In September 1991, while Craig and Rogers were conducting their investigation, they enlisted the help of forensic artist Lois Gibson from the Houston Police Department to create a reconstruction of what Charles Rogers might look like today. They compared this reconstructed image of Rogers with photographs of two other individuals, Harrelson and Holt, alongside the photos of the three tramps. Gibson, who holds the 2017 Guinness World Record for the most identifications made by a forensic artist, confirmed the likelihood that the three men arrested at Dealey Plaza were indeed Rogers, Harrelson, and Holt. Three months later, in a 1991 article discussing Oliver Stone's film "JFK," Chauncey Holt gained national attention for various claims regarding the assassination of President Kennedy. He alleged that he was one of the three CIA operatives photographed as the "tramps." Holt also stated that he was with Harrelson in Dealey Plaza on the day of the assassination.

In 1992, journalist Mary La Fontaine uncovered arrest records that the Dallas Police Department had initially released in 1989. These records identified three men: Gus W. Abrams, Harold Doyle, and John F. Gedney. According to the arrest reports, the men were "taken off a boxcar in the railroad yards right after President Kennedy was shot." They were detained as "investigative prisoners," described as unemployed and passing through Dallas, and were released four days later. An article written by Ray and Mary La Fontaine in the Houston Post on February 9, 1992, prompted an immediate search for the three men by the FBI. Less than a month later, the FBI reported that Abrams was deceased, and interviews with Gedney and Doyle yielded no new information regarding the assassination. Despite the Dallas Police Department's identification of the three tramps as Doyle, Gedney, and Abrams, the photographs taken at the time of their arrest have fueled speculation regarding their identities, as they appeared well-dressed and clean-shaven, which is unusual for rail riders.

Gardeniers

The second book that provided much of my research on Charles Rogers is "The Ice Box Murders," written by forensic accountants Hugh and Martha Gardenier in 2003. It is regarded as the most comprehensive independent investigation into the killings to date. What started as an effort to document one of Houston's most bizarre and unsolved crimes evolved into an in-depth exploration of corruption, cover-ups, and conspiracy theories. The Gardeniers spent years reviewing surviving police reports, medical examiner documents, and archival newspaper articles. They also interviewed neighbors, former coworkers, and retired officers who were involved in the original investigation from 1965.

Records revealed that Edwina Rogers took out a home improvement loan on April 6, 1964. The home renovations she contracted for were not completed, and she kept the $1,350.61 borrowed. Edwina Rogers did not have a power of attorney for her son, Charles, who owned the house. Another signature was found on a deed dated May 17, 1962, transferring ownership of two lots on Almeda Road owned by Charles F. Rogers. Construction on the Astrodome, located nearby, began four months before these lots were sold. In reality, Fred Rogers signed Charles’s name on the deed and kept the proceeds. The Gardeniers shared further insights into the troubled family dynamics within the Rogers household, suggesting that Fred had been abusive toward Charles. They believed that the crime scene showed clear signs of careful planning and precision. The couple theorized that the murders were not impulsive acts of rage but rather deliberately planned acts of revenge.

Their research also explored Charles's connections to the CAP. Through interviews with former CAP members, the Gardeniers confirmed that both Rogers and Ferrie had interacted during several joint training sessions. Both men were proficient in radio operations and shared anti-communist views during the height of Cold War paranoia. This finding was among the first documented links connecting Charles Rogers to individuals involved in the JFK conspiracy. While the Gardeniers consider the "three tramps" theory, proposed by private investigators John Craig and Philip Rogers, absurd, they acknowledge that it is highly probable that Charles Rogers had connections to the CIA.

The Gardeniers also managed to establish a connection between Charles and Anthony Pitts. Charles Rogers sold his Cessna 140 as part of a trade for a Cessna 172. This transaction involved Charles, Francis Ragsdale, Walter S. Fullwood, and Anthony Pitts. According to the Gardeniers, Ragsdale transferred the title of the Cessna 140 to Fullwood on May 29, 1959. Later, the plane was retitled in Pitts’s name after he obtained his pilot’s license. Additionally, the Gardeniers mentioned that Charles had a girlfriend named Jean, who worked as a secretary at Fluor Corporation. On June 24, 1965, Charles arrived at her workplace under the guise of "Anthony Pitts." Jean reportedly assisted him in fleeing. A getaway car had been staged behind the building by one of Charles’s associates, and from there, he vanished—most likely heading to Mexico.

After that point, tracing Charles' movements became significantly more challenging. His name resurfaced only through a man named John Mackey, an American entrepreneur managing a mining operation in Mexico and Honduras for Texas investors. Mackey was in search of a skilled geophysicist to direct drilling operations, and Charles—renowned for his expertise in locating oil and gold—seemed like the perfect fit for the job. According to the Gardeniers, when the Ice Box Murders captured national attention, those who had employed Charles chose to remain silent. As Hugh Gardenier later remarked, they were profiting too much from his talents to report him, referring to him as their “golden goose.”

John Mackey's widow recalled an incident when the Honduran police arrived at their home to report a gruesome discovery: the body of an American geophysicist found downstream in a river. The man had been killed with a pickaxe during what authorities described as a wage dispute. His body was severely decomposed—damaged by the tropical heat and fish in the water—making identification impossible. Mackey told the police he had no idea who the man could be. However, the Gardeniers believed this might have marked Charles Rogers’s final chapter—a violent end that echoed the brutality of his parents’ deaths.

In 2023, I contacted Hugh and Martha Gardenier to ask if they still had access to their original research materials. Because the murders of Fred and Edwina Rogers are classified as an open investigation, the Houston Police Department refuses to release any additional records. Many of the detectives and family members that the Gardenier couple interviewed have since passed away, leaving behind only fragments of evidence and speculation. Hugh expressed that he still believes there is more to uncover in regards to Honduras, and possibly in the story of Anthony Pitts. However, he emphasized that the account presented in "The Ice Box Murders" remains the most comprehensive version of the events that have been assembled. To borrow a line from Oliver Stone's film "JFK," “It’s a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.”

Sources

Craig, John R.; Rogers, Philip A. (1992). The Man on the Grassy Knoll. Avon Books.

Gardenier, Hugh; Gardenier, Martha (2003). The Ice Box Murders. Redbud Publishing.

https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/Grisly-Ice-Box-Murders-7251178.php

“Nationwide Search Begun for Son, 43.” The Amarillo Globe-Times, June 24, 1965.

“Houston Recluse Sought In Butchering of Parents.” The Victoria Advocate, June 25, 1965.

https://www.aarclibrary.org/publib/jfk/hsca/reportvols/vol9/pdf/HSCA_Vol9_4_Oswald.pdf

https://www.history-matters.com/archive/jfk/hsca/reportvols/vol10/html/HSCA_Vol10_0055a.htm

https://www.history-matters.com/archive/jfk/hsca/lopezrpt/html/LopezRpt_0004a.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Rogers_(murder_suspect)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Harrelson

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_tramps

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Ferrie

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lee_Harvey_Oswald

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guy_Banister

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fair_Play_for_Cuba_Committee

https://www.archives.gov/files/research/jfk/releases/docid-32263970.pdf