Carla Walker

13 min read

Carla and Rodney

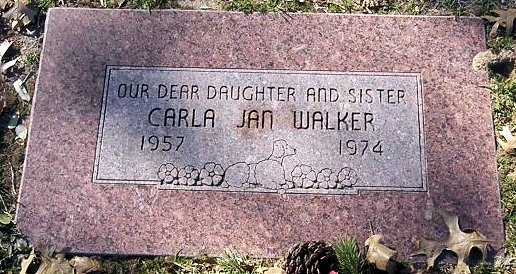

Carla Walker was born on January 31, 1957, to parents Leighton and Doris Walker. In 1974, Carla was seventeen and attended Western Hills High School in Benbrook, Texas, near Fort Worth. She was well-liked by all her peers and was the type of girl who smiled and said hello to everyone in the hall. Carla was 4'11 and 110 pounds, with a thick mane of golden hair. Though petite, her family described her as fiery, sassy, and stubborn. She was a cheerleader and tennis team member. Her boyfriend, Rodney McCoy, eighteen, was a Western Hills senior, captain, and quarterback of the varsity football team.

The couple had been dating for about a year by 1974. Rodney planned to attend Texas Tech University in Lubbock, and Carla planned to follow him. Rodney had even given Carla a promise ring. The Walker family loved Rodney like one of their own. Over the past year, he came over almost every night to study with Carla and became very close with Carla's older sister, Cindy, and her boyfriend. The two couples often listened to records in the sisters' shared bedroom.

On February 16, 1974, Rodney arrived at the Walker home to take Carla to the high school's Valentine's Day dance. She descended the stairs wearing a powder blue prom dress with white ruffles. Rodney and Carla hopped into his mother's car, a 1969 Ford LTD, and headed to the school cafeteria decorated with pink streamers and paper hearts. The theme was "Love is a Kaleidoscope." When the dance ended, around 11:30 pm, Rodney invited another couple to cruise Camp Bowie Boulevard with him and Carla. They stopped at a couple of places where other teens were known to frequent, Mr. Quick Hamburgers and Taco Bell. Later, after dropping off the others, Rodney and Carla drove to a nearby bowling alley, Brunswick Ridglea Bowl, so that she could use the bathroom. When she got back into the car, the couple began to make out.

Carla leaned back against the passenger door, using her purse as a pillow, and Rodney climbed onto her. Suddenly, the passenger door swung open, and someone was hitting Rodney in the head with the butt of a pistol. Barely conscious, Rodney heard a man say, "You're coming with me, aren't you, sweetie?" He reached for Carla and tried to pull her back into the car, but the man pointed the pistol in Rodney's face and pulled the trigger. There were three clicks. At some point during the bludgeoning, the gun's magazine had dislodged and fallen onto the parking lot. He later recalled: "Carla was screaming, 'Quit hitting him,' so my assumption, he hit me several times. Blood was just flowing down in my eyes and my face and everything, and it was like I was paralyzed." "Rodney, go get my dad," Carla said. "Go get my dad."

Rodney regained consciousness sometime around 1 am. He sped to the Walkers' home, less than a mile away. He drove over the curb onto the front lawn and slammed on the brakes. Carla's parents, Leighton and Doris, were still awake, playing dominoes in the dining room with relatives. Carla's little brother Jim, who was twelve years old, and her elder sister, Cindy, who was eighteen, were in the living room, watching television. With blood dripping down his face, Rodney began banging on the front door. "Mr. Walker, they've got her," he shouted frantically. "They're gonna hurt her bad."

Investigation

Officers soon arrived at the bowling alley. Searching the parking lot, they found Carla's purse and the magazine clip from the attacker's weapon. Other cops drove the surrounding streets looking for any sign of Carla. Many more joined the search in the morning, including her friends and family. Rodney told police that he caught a glimpse of Carla's abductor, a white man standing about 5'10 and weighing around 175 pounds. Rodney said he had short brown hair and was wearing a vest. When classes resumed on Monday morning, detectives visited Western Hills High. They studied contact sheets of photos taken at the dance, looking for anyone who seemed out of place. They stopped kids in the hallways, asking if they knew anyone who would want to hurt Carla.

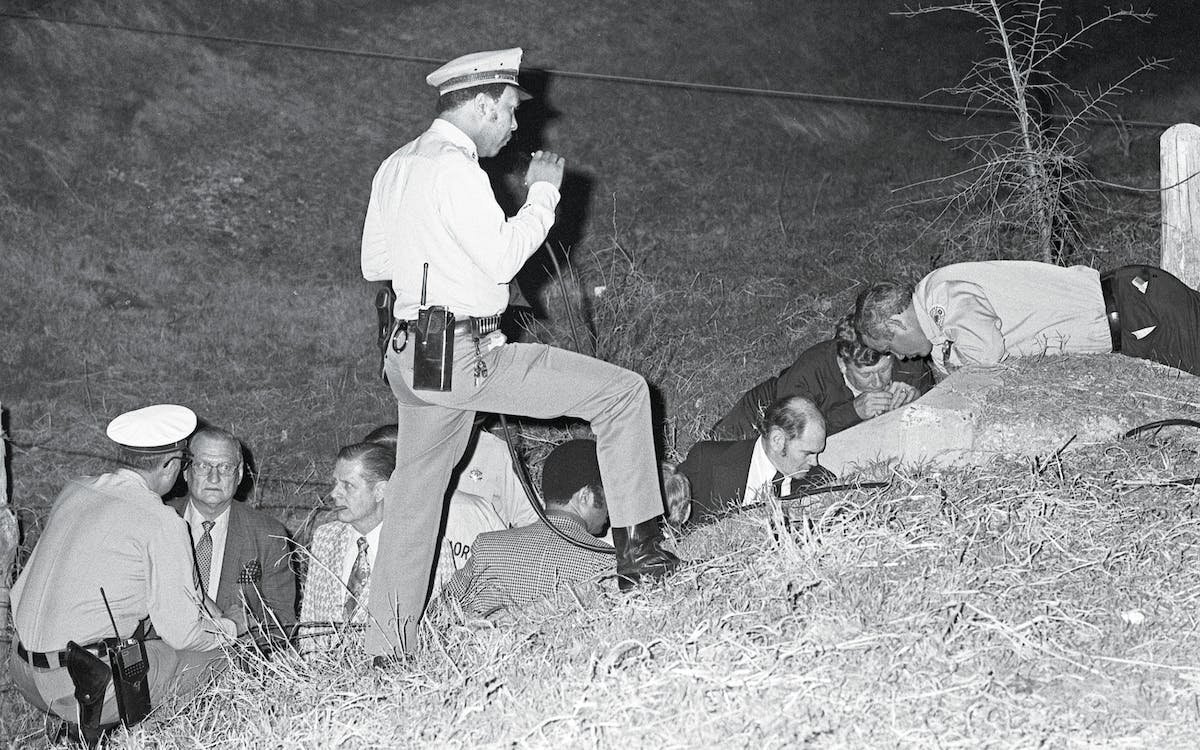

On February 20, four days after Carla Walker's disappearance, two officers were driving along a remote two-lane road near Benbrook Lake, about five miles southwest of the bowling alley. They spotted a draining ditch and pulled over to peer inside. They saw a young woman lying on her back, her face and neck covered with scratches and deep bruises. Her blue dress was bloody and ripped in several places, her bra was pushed up above her breasts, and her underwear and pantyhose were wadded together at the culvert entrance.

Carla's parents were asked to come to the morgue to identify the discovered body. Jim went with them. "Someone took Mom and Dad down the hall to look at her, and my mom started to scream," he said. "I had never heard anyone make a sound like that. It was like an animal sound. That will stay with me for as long as I live."

Police searching the culvert where Carla’s body was found

Credit: Fort Worth Star-Telegram/The University of Texas at Arlington Special Collections

The autopsy suggested that Carla had been alive for two days following her abduction and had been beaten, tortured, raped, and strangled to death. Toxicology reports also showed she had been injected with morphine. Lab technicians found traces of bodily fluid, but forensic science in 1974 did not yet exist to identify a person from their DNA. Police set up a 24-hour tip line and received hundreds of leads; unfortunately, none were helpful to the case. One of the few clues they had was the Ruger .22-caliber pistol magazine. So they asked the federal government's Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms to provide the names of anyone living in Fort Worth who had purchased that model. The ATF devised a list of a few dozen people, and the task force set out to interview each of them, but they all had alibis for the night of Carla's murder.

It was almost a year later before investigators identified their first suspect, Tommy Kneeland. Kneeland had been convicted and sentenced to 550 years for killing Nancy Mitchell, 27, in Kermit, Texas, on September 15, 1970. Mitchell disappeared while her two children slept, and her clothes were found cut up several days later along a highway. Her remains were found in a shallow grave in June 1971. Kneeland was also sentenced to two life terms for killing a 17-year-old girl and a 15-year-old boy in Fort Worth on July 1, 1972. Both victims' throats were cut, and the girl was raped. Then, on April 23, 1974, Kneeland kidnapped a girl in Arlington and tried to rape her, but his truck got stuck in the mud, and the girl escaped. Investigators questioned him, and he confessed to all the slayings, disowning the murder of Carla Walker. Over the next few years, several other men were indicted for the crime but would later recant their confessions. Despite detectives working every lead they had, the case turned cold for nearly 45 years.

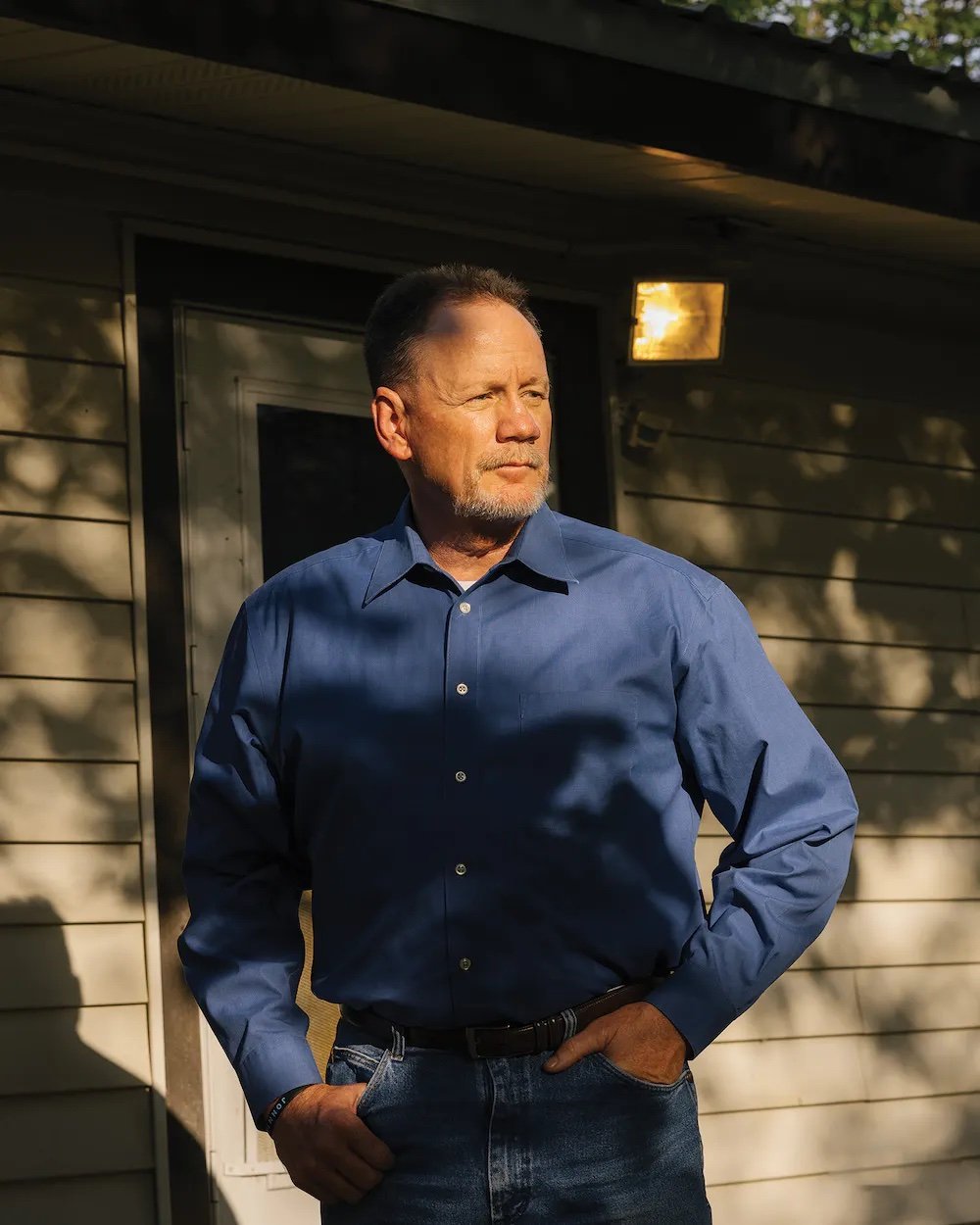

Jim

Carla's family never gave up searching for her, especially her little brother, Jim. He graduated from Western Hills High and attended Sam Houston State University, where he read books on serial killers and took courses in abnormal psychology to understand "the criminal mind." After college, Jim returned to Fort Worth and applied to become an officer. "My plan was to get promoted to detective, get my hands on Carla's files, and find her killer," he told Texas Monthly reporter Skip Hollandsworth. During training at the academy's firing range, however, Jim noticed something wrong with his eyesight. A doctor later diagnosed him with a congenital eye condition, forcing him to drop out of the academy.

Jim Walker

Credit: Trevor Paulhus

Sadly, Leighton and Doris Walker passed away before anyone was convicted for Carla's murder. So, Jim purchased his parents' home and moved into it with his wife. "I wanted to be there in case somebody ever got a conscience at three in the morning and showed up to confess," he said. Jim regularly called the Fort Worth Police Department's cold case unit to ask about developments in Carla's murder and was always told that nothing new had emerged. Until 2019, when Jim was 57 years old, a new set of detectives, Leah Wagner and Jeff Bennett, had taken over the case.

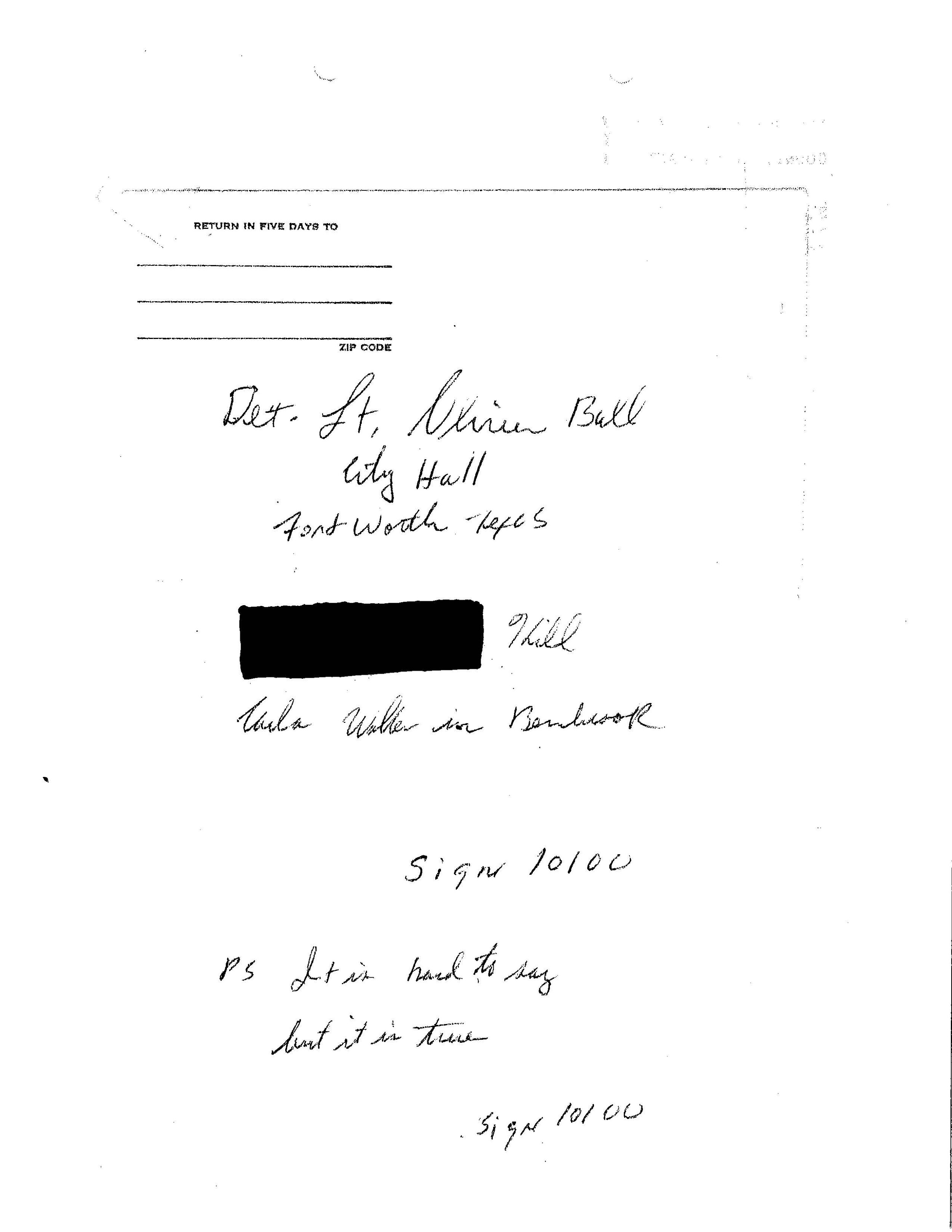

Detective Bennet came up with a list of roughly eighty people of interest he wanted to reinterview after meticulously looking through Carla Walker's files. To try and locate new witnesses, the Fort Worth police department posted a redacted version of an anonymous letter on social media that had not been shared with the public before. The letter read in part: "killd Carla Walker in Benbrook Sign 10100" and "PS It is hard to say, but it is true Sign 10100." A Fort Worth police spokesman told the media they weren't sure what it meant but thought it may be related to a police code for "dead body."

They received several leads, including one from a woman who claimed that her ex-husband had grown up in the same neighborhood as Carla and had kept a stash of newspaper articles about her murder. The man, however, proved he had been out of town the weekend Carla was murdered. The detectives needed physical evidence; the best they could hope for was the killer's DNA. Thankfully for Wagner and Bennett, Carla's clothes had been carefully preserved in the police department's evidence lab. However, DNA tests can cost as much as $20,000, and that money often goes toward active cases.

The Murder Weapon

A Western Hills High School graduate, Dianne Kuykendall, listened to Gone Cold Podcast - Texas True Crime and the show's episodes on Carla Walker. "We didn't know each other at all, but she had always smiled at me in the hallway. She made me feel good—the popular girl talking to someone like me. Listening to the podcast, I thought, 'I wish there was some way I could pay her back.'" Dianne decided to fly to Nashville to attend CrimeCon and brought eighty copies of a flyer she had written about Carla's case. Passing them out to attendees and celebrities such as Dateline's Keith Morrison, Fox News' Nancy Grace, and Paul Holes, a retired homicide investigator who had helped solve the Golden State Killer case and hosted a true crime show on NBC's Oxygen network. Holes was intrigued by Carla's case, and his producers called Wagner and Bennett. Oxygen was willing to pay $18,000 to cover the DNA testing cost on Carla's clothes.

Technicians at the Serological Research Institute in California found semen on Carla's bra strap and developed a complete DNA profile. Then, they uploaded it to CODIS, a nationwide law enforcement database containing millions of criminals' DNA. CODIS, however, couldn't find a match. So, Holes and his producers contacted a Texas lab specializing in genealogical mapping, but technicians there had no luck either. Because the other laboratories had used so much of the DNA from Carla's bra strap in their tests, there was hardly enough left for further attempts. Then, Holes introduced Detective Wagner and Bennett to David Mittelman, CEO of Othram, a forensic DNA testing lab near Houston. Othram reconstructed the DNA sample's genome using state-of-the-art parallel DNA sequencing. Othram then uploaded the data from the sample onto GEDmatch, an online service to compare autosomal DNA data files from different testing companies.

On July 4, 2020, Mittelman called Bennett, saying, "We've connected the DNA to a particular family tree. The last name is McCurley." Bennett looked through his notes, took a deep breath, and asked Mittelman if anyone in that family tree was named Glen Samuel McCurley. Yes, said Mittelman, there's a Glen Samuel McCurley, but he died in 1972. However, there is a Glen Samuel McCurley Jr., and he had been living in Fort Worth at the time of Carla's killing. According to Bennett's case notes, McCurley was on the list of suspects who owned a .22 Ruger handgun in 1974.

Glen McCurley

Records show that Glen McCurley Jr. had stolen a car in Abilene, Texas, in February 1961, then abandoned and stole another vehicle. The state highway patrol caught up to him and shot out one of his tires. Glen then drove into a vacant lot and tried to run away on foot, but police quickly apprehended him. In court, he pleaded guilty and received a two-year sentence. Glen was released early, in the spring of 1962, when he was nineteen, and eventually moved to Midland. On February 16, 1963, Glen married Judy Watson, and he secured a job as a truck driver for the U.S. Postal Service, with a route to the Dallas-Fort Worth area. In 1972, after the birth of their two sons, the McCurleys moved to West Fort Worth. Glen got another job as a trucker, hauling concrete slabs to construction sites, and Judy worked at Ridglea West Baptist, where the family attended church.

In March 1974, two detectives arrived at the McCurley's home. They were investigating the death of Carla Walker, and his name appeared on a list of people who had purchased a Ruger .22 pistol, the murder weapon. Their home was also just a few blocks from the bowling alley where Carla was abducted. When the officers asked about the gun, Glen said it had been stolen six weeks ago from his truck while fishing. He then agreed to come downtown and take a polygraph test, which he passed and was eliminated as a suspect. Over the years, Glen McCurley had maintained a good reputation in his community and had no further contact with the police.

On July 7, 2020, three days after receiving the call from Othram, Fort Worth police collected three items from a trash can on the curb of the McCurley's home and had it sent for DNA testing. The results came back matching the male profile that Othram had helped identify. Detective Wagner and Bennett showed up at the residence unannounced on September 10, telling the Mccurleys that the murder investigation had been reopened and they were contacting everyone interviewed by the police in 1974. Wagner then asked Glen if she could take a DNA sample from him, explaining it would be the easiest way to eliminate him as a suspect. Hesitating at first, he eventually grabbed a pen, signed a consent form, and opened his mouth so Wagner could swab the inside of his cheek. On September 16, lab technicians confirmed that the DNA from Glen McCurley matched the DNA found on Carla's bra.

Aerial view of Glen McCurley’s neighborhood in 2022

Credit: Trevor Paulhus

Arrest

On September 21, 2020, the U.S. Marshals North Texas Fugitive Task Force, a unit specially trained to arrest high-risk criminals, arrived at the McCurley’s home. They placed Glen under arrest, and he waived his right to have a lawyer present during his interrogation. Wagner and Bennett walked in and set a photo of Carla on the table. "We are here to discuss the murder of this young lady." Glen looked briefly at the picture. "I don't know who she is," he said. Bennett pointed at the photo and said, "Mr. McCurley, can you look at that picture and just tell us for sure that you do not know who she is?" Glen picked it up and examined it more closely. "I've never seen her before," he said. "I wouldn't know her if she was standing beside me." Glen continued denying he had ever met Carla for over an hour before he eventually cracked.

With his gaze fixed on the floor and tears in his eyes, Glen McCurley told the detectives that on the afternoon of February 16, 1974, he had consumed whiskey and beer for "several hours." Then, he said he began driving around and "parked in some parking lots." At one point, he went to "the bowling ball place." He told the detectives he'd heard a girl "screaming" in a nearby car. "I went over there to see if I could help. This big guy had her up and against the door, jerking her around."

Glen said he opened the front passenger door, got into "a tussle" with the boy, pushed him off Carla, led her back to his car, and then drove her to another parking lot. "She started hugging me, thanking me, and one thing led to another," said Glen. "I did have sex with her." He claimed he then let her out of the car. "I don't remember too much from there on."

Wagner told Glen that they had learned Carla was a virgin. If she wasn't having sex with her boyfriend, Wagner said, "people are going to have a really hard time believing that she was going to willingly have sex with you." Glen repeatedly denied that he had raped Carla but did say that after they finished having sex, he started choking her because he was afraid "she'd tell on me or something." But he stated Carla was still alive when he drove away. The more Glen McCurley talked, the more confounding his claims became, and investigators wondered if he was mixing up the details of Carla's killing with a different murder.

In May 2021, prosecutors announced that they would not seek the death penalty against Glen McCurley, by then seventy-eight and in poor health. If convicted, however, he would face a maximum life sentence in prison. After speaking to his court-appointed attorneys, Glen pleaded not guilty. His attorneys argued in their court filings that the Othram lab's DNA test was flawed and that Wagner and Bennett had coerced Glen into a false confession. Prosecutors, however, persuaded a judge to set the bond at $500,000. "To just look at him and say he's sick, or he is old, or he hasn't had a criminal history isn't the proper analysis in this case," said Kimberly D'Avignon, an assistant district attorney with the Tarrant County District Attorney's Office. "You have to go back and consider the heinousness of this crime and the impact it had on Fort Worth in 1974. In many ways, Fort Worth was never the same after Carla was killed."

The trial began in August, and Rodney McCoy was brought in to testify about the night Carla vanished. Prosecutors D'Avignon and Emily Dixon unfolded Carla's powder-blue dress and showed it to the jury. They also played three hours of the videotaped interview and confession. Prosecutors then presented a surprise piece of evidence, the .22 Ruger pistol Glen had claimed was stolen. Police had discovered it while searching his home, hidden in a compartment above a door. On the third day of the trial, Glen McCurley changed his plea to guilty, and the judge sentenced him to life in prison on August 24, 2021.

Where are they now

After graduating high school, Rodney McCoy moved to Alaska to work on an oil rig and told his family that he needed to get as far away from Fort Worth as possible. He eventually returned to Texas and is happily married.

Hoping to raise money to pay for DNA testing of more cold cases, Detective Bennett formed a nonprofit foundation called the FWPD Cold Case Support Group. Jim Walker joined the board, too, promising to donate some of the profits from selling his family home. Telling interviewers he is finally ready to let things go.

Cindy Walker named her daughter after her sister, who now bears the same short legs and sassy personality as Carla once did.

Glen McCurley is imprisoned at the Gib Lewis Unit in Woodville, Texas, and will be eligible for parole on March 21, 2029. He has since retracted his confession, telling reporter Skip Hollandsworth that he only pled guilty because no one would believe him. Investigators believe Glen may have been involved in the rapes and murders of several other young women in the Fort Worth area in the 1970s and 1980s, although he has not been charged with any additional crimes yet.

Sources

https://www.texasmonthly.com/true-crime/glen-mccurley-carla-walker-murder/

https://hometownbyhandlebar.com/?p=35110

https://twitter.com/fortworthpd/status/1119264366443094016

https://www.nbcnews.com/dateline/watch-dateline-episode-after-dance-now-n1288341

https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc1794739/m1/1/

https://www.oxygen.com/dna-of-murder/crime-news/carla-walker-murder-cold-case-cheerleader

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murder_of_Carla_Walker

https://www.nbcdfw.com/news/local/watch-live-carla-walker-cold-case-murder-trial-enters-third-day/2725579/

https://inmate.tdcj.texas.gov/InmateSearch/viewDetail.action?sid=01085550

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/34494837/carla-jan-walker